|

While the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta was celebrated last week on both sides of the Atlantic by a series of major events and extensive media coverage, Pocklington & District Local History Group focussed on the numerous local links to ‘The Great Charter’ at its June meeting. While the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta was celebrated last week on both sides of the Atlantic by a series of major events and extensive media coverage, Pocklington & District Local History Group focussed on the numerous local links to ‘The Great Charter’ at its June meeting.

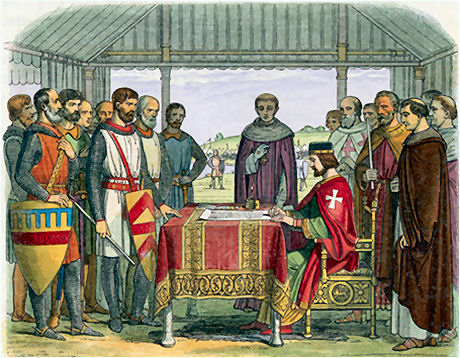

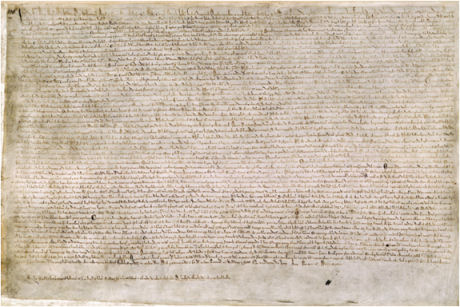

Magna Carta is one of history’s great myths – it was a peace treaty to bring about a truce between King John and the country’s leading barons who were locked in a civil war conflict. The actually 1215 treaty lasted only ten weeks before it was annulled by the king. However, it was revised and reissued several times in the succeeding century whenever the crown was in trouble, and it somehow transcended into becoming the bedrock of western democracy, liberty and justice.

However, it was the local connections of some key personalities involved in the charter that occupied the history group last Thursday.

Predominant was the monarch himself, King John, who was actually lord of the manor of Pocklington at the time of Magna Carta. John was the fifth son of Henry II, and never expected to be involved in sovereignty; but when three of his older brothers died young it thrust him forward to be heir to the throne to his brother, King Richard. Predominant was the monarch himself, King John, who was actually lord of the manor of Pocklington at the time of Magna Carta. John was the fifth son of Henry II, and never expected to be involved in sovereignty; but when three of his older brothers died young it thrust him forward to be heir to the throne to his brother, King Richard.

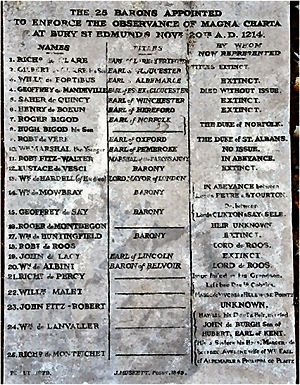

Though John has gone down in history as ‘Bad King John’, a manipulative, cruel and lecherous ruler who lost England’s vast French possessions, he was an able administrator and good record keeper, and his pipe rolls contain numerous references to Pocklington and district. In addition several of the 25 Magna Carta barons, the key nobles chosen to enforce the treaty and regarded as the originators of Parliamentary government, had local links.

|

Coat of arms of William de Mowbray |

| By Rs-nourse (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons |

Though John plotted to seize his brother’s throne in the early 1190s, he was subsequently reconciled with Richard I who gave him the manor of Pocklington in 1197. So when John became monarch on the death of his brother two years later he was already Lord of Pocklington as he was crowned King of England.

Thanks to his meticulous record and book keeping we know quite a bit about Pocklington and its agriculture in the early 1200s. At the time Pocklington had a population of around 500 and All Saints was still under construction; the core of the present church, but with a central tower, not at the west end as now, is said to have been completed in 1220. The town was surrounded by six open fields, divided into strips, had three mills and a communal oven. Its clay land was highy valued in Medieval times and John devolved the farming of his manorial lands to a group of Pocklington’s leading yeoman – a sort of early farming cooperative. John charged the Pocklington farmers £45 and a palfrey horse each year, then added an additional levy as in addition to barley and oats they were mainly raising pigs, and not enough of the expected quota of cows, boars and oxen.

The Magna Carta signed by King John in 1215

It appears that the men of Pocklington tried to fiddle the payment due to John, so the manorial farm was later rented to favoured nobles and John gave a portion of Pocklington land, worth £20 annually, to William de Forz on new year’s eve 2014.

Soon afterwards de Forz married Aveline de Montfichet, sister of another Magna Carta baron, Richard. De Forz was initially a supporter of King John but then joined the rebel barons, and he subsequently changed sides numerous times depending on whoever was in ascendancy. Though he was so frequently against the crown, he was richly rewarded by the king, and some sources have even suggested that he could have been one of King John’s many illegitimate offspring. De Forz became lord of the whole manor of Pocklington for a token annual payment to the king of a sparrowhawk.

One of de Forz’s closest friends was Magna Carta baron, Robert de Ros, who had deep local roots. His mother, Rohese Trussebut, was born at Warter, and the Trussebuts were long standing owners of Warter and the founders of Warter Priory. De Ros inherited the Trussebut estates from his grandfather and had a manor house at Storwood, at the side of the Pocklington canal, and you can still see the moat and earthworks of the site. His estate included Seaton Ross, half the manor of Market Weighton and later holdings in the soke of Pocklington in 1220s (the soke was land controlled by Pocklington but was situated in nearby villages).

The group of northern barons at Runneymede also included the diminutive Eustace de Vesci, whose estates included Melbourne, Thornton, Hotham, Cliffe and Holme upon Spalding Moor, while his grandfather, Robert de Stuteville, had held the farm of Pocklington early in the century. Related by marriage to de Ros, Vesci was a leading rebel baron who is said to have plotted to assassinate King John in 1213.

However, the strongest connection between Pocklington and Magna Carta came when another of the 25 barons, William de Mowbray, claimed that he owned the manor of Pocklington during the charter’s negotiations. De Mowbray asserted that he had hereditary rights to ‘the custody of York castle and the forest of Yorkshire, and to the tenure of the manor of Pocklington in demesne’. It prompted King John into asking the Sheriff of Yorkshire to investigate the claim, which resulted in the manor be confirmed as belonging to the king.

Another local link person was Walter de Gray, who witnessed the 1215 document and became Archbishop of York the following year. De Gray is credited with building the original archbishop’s summer palace at Bishop Wilton in the 1220s; and he was a leading church reformer who took the vast Saxon minster parish of Pocklington that included Allerthorpe, Barmby Moor, Bielby, Givendale, Hayton, Kilnwick Percy, Meltonby, Millington, Ousethorpe, Thornton and Yapham, splitting it into four smaller separate parishes in 1252.

While the original Magna Carta of 1215 was soon scrapped, it was a time of great turmoil in England. King John died in 1216 at a time when a Fench army of invasion occupied a third of the country and was pressing for victory. John’s son, who had been present at Runnymede in 1215, became King Henry III, aged just nine, and his regency council reissued the charter twice, in 1216 and 1217, as a rallying point for the royal cause

Carvings in Pocklington Church of King Henry III

and his wife Queen Eleanor of Provence.

The French were defeated and Henry III produced a new version of Magna Carta, with the initial 63 clauses reduced to 37, when he came of age in 1225. This is the document that is recognised as the iconic charter that did so much to develop democracy around the world. Henry III also had significant links with Pocklington, taking the manor back when William de Forz again rebelled and giving it to his new queen, Eleanor of Provence, as part of her marriage dowry in 1236. Henry also granted the first royal charter for a fair at Pocklington in 1245.

The final reissues of Magna Carta, in 1297 and 1300, came during the time of the next King of England, Edward I. He visited Pocklington in 1291, 1293 and 1298 (twice) and spent much of the later years of his reign fighting the Scots, which included establishing Kingston upon Hull as a base to attack Scotland. And he used the manor of Pocklington to do a swap with Meaux Abbey for their land at the mouth of the River Hull and found his port on the Humber in 1294.

Phil gave a talk to the P&DLHG on 18th June 2015, entitled "Pocklington & The Great Charter - local links to Magna Carta 800 years on" Phil gave a talk to the P&DLHG on 18th June 2015, entitled "Pocklington & The Great Charter - local links to Magna Carta 800 years on"

|