Pocklington in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries

Background

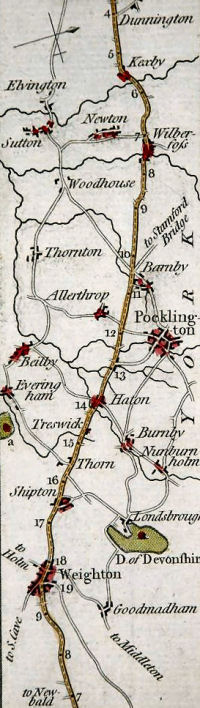

Pocklington is in the East Riding of Yorkshire, some thirteen miles east of York slightly to the north east of the turnpike from York to Beverley, now the A1079, which is close to the line of the Roman road from Brough to York. It was described as having burgesses in Doomsday; its minster church was then the centre of a large parish; its early charters for fairs and markets and a planned thirteenth century market place reflect its early importance as a marketing centre. By the eighteenth century it had long ceased to be a centre for the wool trade but corn milling had been joined by malting and tanning as its principal industries. The fact that East Riding Quarter Sessions were held at Pocklington as well as Beverley up to the later part of the seventeenth century is a reminder that it had also been an administrative centre and Neave considered that it 'had the aura of a minor social centre in the 1730s and 40's'.1 It continued to be a locally important market centre in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In 1743 the population of the town was said to be 943; by 1821 it was recorded as 1,962 more or less in line with the national increase. In 1831 it was 2,048, rising to 2.323 in 1841. Pocklington is in the East Riding of Yorkshire, some thirteen miles east of York slightly to the north east of the turnpike from York to Beverley, now the A1079, which is close to the line of the Roman road from Brough to York. It was described as having burgesses in Doomsday; its minster church was then the centre of a large parish; its early charters for fairs and markets and a planned thirteenth century market place reflect its early importance as a marketing centre. By the eighteenth century it had long ceased to be a centre for the wool trade but corn milling had been joined by malting and tanning as its principal industries. The fact that East Riding Quarter Sessions were held at Pocklington as well as Beverley up to the later part of the seventeenth century is a reminder that it had also been an administrative centre and Neave considered that it 'had the aura of a minor social centre in the 1730s and 40's'.1 It continued to be a locally important market centre in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In 1743 the population of the town was said to be 943; by 1821 it was recorded as 1,962 more or less in line with the national increase. In 1831 it was 2,048, rising to 2.323 in 1841.

Who ran the town?

The Vestry records that survive for Pocklington from 1819 2 suggest that there was a well defined group who considered it their duty to govern the town and duly did so. Predominately it was those who made their living in the town by trading activities who ran it. In contrast, for example, to the small East Riding town of South Cave, there were relatively few farmers involved in the running of Pocklington.

Although the major local gentry had some influence, the indications are that those running the town had a very wide degree of independence. At Pocklington in 1759 the Lord of the Manor may have owned over 30 per cent of the land in the parish. The percentage of the land area probably remained unchanged throughout the period but by 1824 it may only have represented 20 per cent of the total value. More significantly, throughout the period the Lord of the Manor appears to have had less than two per cent in value of the property within the town itself.3 The Dolmans who were the Lords of the Manor until the end of the eighteenth century were Roman Catholics and latterly took little part in the affairs of Pocklington.4

This independence is well shown in the voting pattern at Parliamentary Elections. In the election of 1741, Pocklington followed the trend in the East Riding, but what is significant is that a substantial minority, 36%, voted for the other candidate.5One must not over emphasise this independence. If support was to be given to the Yorkshire Association by voters in Pocklington in the 1780s, no progress would be made without the support of the Andersons of nearby Kilnwick Percy. When the Pocklington Canal was built in the early nineteenth century the support of Denison at Kilnwick Percy and Vavasour at Melbourne was needed.6 During and after the second decade of the nineteenth century Denison, who had been the Lord of the Manor of Pocklington since 1792, appeared to flex his muscles. In many ways his actions might be benevolent, but the overall effect was to stress his right to be involved with the affairs of the town.7Nevertheless the relative independence of Pocklington is well illustrated by comparison with New Malton, and the actions of Fitzwilliam in 1807 after the electors of New Malton displeased him by electing a Member of Parliament not to his liking. Some electors were evicted and Fitzwilliam could virtually strangle the trade of the town by raising the tolls on the River Derwent Navigation.8

In considering who ran the town one must remember the influence of the Justices of the Peace and the Quarter Sessions for the Riding. The closing pages of Forster's comprehensive survey of the activities of the East Riding Justices of the Peace in the Seventeenth Century9 gives a clear picture of the wide variety of administrative and judicial functions of the J.P.s, in and out of sessions, in the early years of the eighteenth century. During the seventeenth century the East Riding Quarter Sessions met usually at Beverley but occasionally at Pocklington. In many areas - poor relief, highways, alehouses, and of course law and order it was they who were responsible for making sure that the parish officials did their job properly, and the Chief Constables and parish constables were answerable to them.10

But during the eighteenth century the J.P.s were thinly spread across the Ridings and the difficulties that they could face were vividly described by Sir Edmund Anderson of Kilnwick Percy, near Pocklington, in his contemporary account of the local anti militia riot of 1757. A mob from the whole Wilton Beacon Wapentake, his Wapentake, 'led by their several constables ... forced the whole town of Pocklington (Parsons, Attorneys and all our friends) to go up to Kilnwick’ to demand the return of the local Militia lists. Lady Anderson reasoned with them until Sir Edmund returned later in the day and it was only by the force of his personality that the rioters could be dispersed.11

Neave mentions numerous Quarter Sessions cases relating to residents of Pocklington in the first half of the eighteenth century but none thereafter.12 It is possible that from then onwards the townspeople were usually able to resolve problems without involving Quarter Sessions. In the 1820s the Pocklington Vestry Resolution Book recounts the sorry tale of Mr George Clarkson who, whilst a Highway Surveyor, had charged two labourers against the township saying that they were working on the highways whilst, in reality, they had been employed on Mr Clarkson's farm. But no criminal prosecution for this fraud appears to have been brought. The matter was dealt with within the town.13 This self-regulation is well illustrated by a note in the diary of Robert Sharp at South Cave. When a visitor to Cave Fair in 1827 declined to pay for his lodgings, Sharp, then the local constable, desired some of 'the Crowd' to turn him out of town. After the visitor 'landed safely in the beck, where he had a cool bath not very clean', he then found that he had the three shillings and sixpence that was needed.14

By the 1820s local magistrates such as Robert Denison of Kilnwick Percy appear to have been using their status as a Justice of the Peace to assert their authority. - Denison was also the Lord of the Manor at Pocklington. In 1823 Denison was on the Committee dealing with the revaluation of Pocklington for rating purposes. Since he was the major landowner this was only to be expected. But he also led the Committee that sorted out George Clarkson's activities, and when an assistant overseer was to be appointed in 1824 he was in the chair and he and his father 'allowed' the decision to appoint James Stadders to that post in 1826. He was not however present in 1826 when the Vestry decided to reduce the rateable value of the Tolls of Pocklington, to which he was entitled, from £20 to £10.15

How was the town run?

The officers of the town were, at least in theory, appointed by and answerable to Quarter Sessions, the Manorial Court or the Vestry. Webb has commented that only a handful of the parishes whose records have been deposited at the Borthwick Institute in York have any vestry minutes prior to the nineteenth century and that the earliest vestry accounts date from 1838.16 He suggests the general pattern was for individual parish officers to render their own accounts for subsequent auditing at an annual vestry meeting. This appears to be what had happened at Pocklington in the eighteenth century, but one can detect the change noted by Webb in the early years of the nineteenth century at Malton, where the vestry for the parish of Old Malton acted, in effect, as the town council. Webb suggests that where vestry minutes do exist they effectively only record matters of particular importance, routine matters are not covered. In fact to describe such records as vestry minutes is somewhat of a misnomer. This can be seen very clearly at Pocklington where a vestry book was started in 1819.17 This book, the Pocklington General Vestry Resolution Book, throws some light on why the changes were made. In 1819 a Vestry Meeting, chaired by George Bagley, the High Constable for the Wapentake, was held specifically to consider the best mode for keeping the parish accounts which 'had been of late very irregularly and improperly kept'. Specific rules were then laid down as to how accounts should be prepared in the future. However in practice these must have been unenforceable and in 1823 George Clarkson's unsatisfactory tenure of the office of Highway Surveyor during the previous year highlighted the problems. Thus in 1824 it was decided a proper person should be appointed 'as an assistant overseer of the poor and surveyor of the highways and collect all lays and assessments pay all bills and keep all accounts relating to the Parish'. James Stadders was appointed and it was agreed 'That a set of books be purchased published by Mr Ashdown of Middlesex for keeping all Parish Accounts with the Books of Instructions'.18

How was the income of the town spent?

Writing in 1856 Sheahan and Whellan said of Pocklington:-

'Considerable improvements have been made within the last quarter of a century; the Market Place has been cleared from obstructions, and rendered more commodious, by the removal of the ancient shambles; by arching over the rivulet, through the bed of which the high road from Malton and Driffield previously past, for more than fifty yards; and by the construction of spacious and well formed roads, which diverge from it in several directions'.19

It is possible that some of these improvements had been made rather earlier than the authors suggest and it is likely that the arching over of the beck was completed by 1828. Since no mention of this is made in the Pocklington Vestry Book it could well be that a substantial part of the cost was met by adjoining owners since their property was thereby improved. Certainly the cost of the improvements to the beck below the town, due to the improvement of what is now known as Thirsk's Mill and the construction of Devonshire Mill in 1808, would not have been met by the town but they could well have been of considerable benefit in that they would have improved the flow of the beck.

The National School at Pocklington was built in 1819 by Dennison, the then Lord of the Manor. The high road to York and Beverley was a turnpike; the canal leading to the town had been built by the Pocklington Canal Company. Thus the money raised from the town's ratepayers for expenditure, other than on poor relief, was modest - £0.14 per head in 1802-3.20

The Pocklington Vestry Book records that a General Meeting was held on 13th August 1823 to consider the rebuilding the oven in the common bake house at a cost of £9.9.0 (£9.45) and this may well be indicative of the matters that were considered important in that year. Certainly work was undertaken in the town on the repair of roads and bridges but the chief focus of the town would have been the church and its maintenance.

Pocklington installed gas lighting in 1834 - Beverley had been lit by gas since 1824. The enabling statutory powers were used to levy a rate and the gas was supplied by a limited company.

Poor relief must have been a matter that those running the towns had high on their agenda, if only because of the amount of money that had to be committed to this aspect of parish expenditure. In a growing town with good employment prospects the demand for poor relief would be less than elsewhere. An expanding town would have a bias to younger age groups; the elderly would be less likely to migrate to the town. And because of the favourable employment situation in the surrounding countryside, migrants coming to the towns would be drawn to the towns by the attractions of well paid employment, rather than having been driven to leave their previous abode because of famine or privation. The favourable rural employment situation is one facet of the deep North / South divide that developed during the early years of the industrial revolution. Mark Blaug looked at weekly wages for agricultural workers between 1795 and 1850 and the data in the Table below is taken from that which he listed in an appendix to his article published in 1963.21

These wage rates were clearly influenced by the wages of industrial workers, but in the East Riding they also reflected the increased employment available as additional land was brought into cultivation as a result of enclosure.

WEEKLY MONEY WAGES OF AGRICULTURAL WORKERS

(£ Decimal)

| |

1795 |

1824 |

1833 |

1837 |

| |

|

|

|

|

| National Average |

0.45 |

0.48 |

0.53 |

0.51 |

| |

|

|

|

|

| East Riding of Yorkshire |

0.55 |

0.62 |

0.57 |

0.60 |

Source : Blaug22

The population of the country as a whole was living longer but it seems likely, for the reasons just mentioned, that in the early years of the nineteenth century, there would have been an increasing number of the elderly and infirm to care for in the town, a situation that would have become an increasing problem as it ceased to enjoy above average growth in population. But there was not the structural poverty, due to low wages - and the consequent high rates of poor relief per head of population - that was to be found in the southern rural counties.23

Eden implies that Pocklington's workhouse dates from before 1775. He found 20 paupers there in 1796 and is likely that most were elderly or infirm. In 1802 the percentage of those relieved who had been in the workhouse was 15 per cent at Pocklington - this was higher than the figure for Yorkshire as a whole, which ranged from 5 per cent to 8 per cent.24

Eden's comment reminds us that this was not a cheap option. The paupers in the workhouse were farmed - the workhouse master was paid a fixed rate per head - in 1796 Eden notes a figure of two shillings a week.25 From details given in 1829 Hastings calculated in 1984 that the weekly fare at the Easingwold workhouse then 'contained some 19,076 calories which compared very favourably with the weekly 18,000 -21,000 calories needed by the modern manual worker'. Likewise the tone of the minute of a Vestry Meeting at Selby in 1830, when Mary Capes was appointed to manage the town's workhouse, implies that the primary concern of those present was not to cut costs.26

Writing of the Old Poor Law in East Yorkshire in 1953 Mitchelson comments:-

'The workhouse was hated by the poor. It was usually a fearful collection of idiots, children, sick and senile people, unmarried mothers and unemployed. Crabbe's savage criticism in his poem The Village (1783) probably gives as true a picture as any of the rural workhouse'.27

Perhaps this was true of Crabbe's native Suffolk, but current research suggests that Mitchelson's comments were heavily influenced by the undoubted, and very understandable, antipathy against the workhouse under the regime that prevailed after 1834, particularly in the southern counties of England. A far more accurate picture is that given by Snell showing the more benign face of the old poor law - at least until the strains in the system emerged in the 1790s, strains that were at their worst in the low waged southern counties of England. It is indicative of the situation in Pocklington as late as 1823 that only 10, out of perhaps 200, ratepayers were assessed at more than two per cent of the total for the township. Together they comprised a little under 40 per cent of the total assessment. Influential they would have been, but pure self interest - and not least the need to avoid damage to their windows - would have caused them to care for the poor of the town in the way their fellow townsmen felt to be appropriate.28 Vagrants do not seem to have been a particular problem at Pocklington - there is no reference to vagrants in the Pocklington Vestry Book between 1819 and 1830.

It is not easy to form an accurate view of the rise in the cost of the relief of the poor during the period.29 The level of contribution from charitable endowments and donations, the rapid rise in population, the migration of younger men and women which left communities with an ageing population, the acute periods of dearth - which were far from uniform across the country, and not least, inflation during the Napoleonic Wars at a rate that would not be seen again until after 1914, all these make accurate analysis at local level very difficult. What is clear is that the true amount of expenditure on the poor rose sharply in the last decade of the eighteenth century, again rose sharply in the next decade, and then more or less stabilised. It is also clear that Yorkshire as a whole was one of the counties that avoided the worst excesses.30

Conclusions

By and large Pocklington was run by a defined elite, with little interference from the local clergy or the local gentry. Improvements to the town may well have been financed by individuals. In part this was a facet of longstanding civic traditions.31

The amount of direct public expenditure was minimal by modern standards. Developments in the towns were generally dependent on finance from individuals. This also extended to day to day expenditure, notably on the relief of the poor, although in this area public expenditure rose sharply during the period. But one must stress that the situation as to poor relief was very different from the pattern that developed in the rural south of England.

Roger A Bellingham

Pocklington, October 2006

1 D. Neave, Pocklington 1660-1914 (First edition, 1971 A footnoted copy of the is deposited at ERYA - DDX 268), 19 and passim; N. Pevsner and D. Neave, The Buildings of England Yorkshire : York and the East Riding, (Second edition, 1995); G.C.F. Forster, The East Riding Justices of the Peace in the Seventeenth Century, East Yorkshire Local History Series 30 (Beverley, 1973), 30.

2 East Riding of Yorkshire Archives (ERYA) PC 52/311- Pocklington General Vestry Resolution Book

3 Powell & Young, Pocklington Pocklington Enclosure Award 18 April 1759. Indexed copy made for James Powell n.d - analysis of tithe annuities; ERYA DDPY/19/9 - Dolman Terrier; Ayer, Survey of Pocklington; ERYA - Land Tax Returns.

4 D. Neave, Pocklington. 18 and 23

5 The Poll for a Representative in Parliament for the County of York in the room of the Right Honourable Henry, Lord Visc. Morpeth deceased, Begun at the Castle of York on Wednesday 13th of January, 1741. (York, 1742).

6 R. Christie, 'The Yorkshire Association 1780-4: A study in Political organisation' Historical Journal, 3, 1 (1960), 156.

7 See Neave, Pocklington, 23.

8 In 1841 the parishes of Old and New Malton together contained 3,833 acres and 1086 houses and other tenements, including shops. Fitzwilliam owned 69 per cent of the former and 67 per cent of the latter. D.J. Salmon (ed.), Malton in the Early Nineteenth Century (Northallerton, 1981), 18 – 19; Duckham, 'The Fitzwilliams and the Yorkshire Derwent', 53-5.

9 Forster, The East Riding Justices).

10 Cf. J.E. Crowther and P.A. Crowther (eds.), Diary of Robert Sharp of South Cave: Life in a Yorkshire Village 1812-37 (1997). xxxix-xli.

11 Neave, Pocklington, 20; D. Neave, ‘Anti-Militia Riots: 1757’ in S. Neave and S. Ellis, An Historical Atlas of East Yorkshire (Hull, 1996)., 124-5. The events at Kilnwick Percy are recounted by Sir Edmund Anderson in a letter dated 29 Mar 1758 held at Lincolnshire Archives Office - And/5/2/1.

12 Neave, Pocklington, 18-19.

13 Pocklington Vestry Book - 18 Dec 1823.

14 Crowther, Sharp, xl and 141.

15 Pocklington Vestry Book, passim

16 The Selby Vestry Book, which dates from 1790, is deposited at North Yorkshire County Record Office - DC/SBU MIC Selby Vestry Book

17 C.C.W. Webb, Guide to Parish Records in the Borthwick Institute of Historical Research (York, 1987), xviii – xix; Pocklington Vestry Book. Malton was, and is, divided into three parishes. The Old Malton vestry minutes deposited at the Borthwick date from 1820.

18 Pocklington Vestry Book - 7 Oct 1819, 18 Sep 1823, 11 Mar 1824, 6 Apr 1824. James Stadders was probably the son of a Pocklington shopkeeper.

19 Sheahan and Whellan’s History and Topography of the City of York; the Ainsty Wapentake; and the East Riding of Yorkshire, J.J. Sheahan and T. Whellan (Beverley, 1856). East Riding, 2, 564-5.

20 Baines’ Directory and Gazetteer of the County of York, E. Baines 2, East and North Ridings (Leeds, 1823) 377; Parliamentary Papers Abstract of Returns Relative to the Expense and Maintenance of the Poor, (1803-04) XIII; The county average was £0.21 in the East Riding, £0.16 in the North Riding and £0.14 in the West Riding.

21 As to the North / South divide, see K.D.M. Snell, Annals of the labouring poor: social change and agrarian England, 1660-1900 (Cambridge, 1985), 1-2; M. Blaug ‘The Myth of the Old Poor Law and the making of the New’, Journal of Economic History, 23 (1963), 182-3.

22 Blaug, ‘Myth of the Old Poor Law’, Appendix D.

23 E.A. Wrigley and R.S. Schofield, The Population History of England 1541-1871 (Paperback edition, Cambridge, 1989), 326 - Table 6.33 and 328 Cf. Blaug, ‘Myth of the Old Poor Law’, 178-183.

24 F,M. Eden State of the Poor,(1795) 881; PP Abstract, (1803-4), 590, 592, 602.

25 Eden, State of the Poor, 881.

26 Selby Vestry Book, 13 Jan 1800, 1 Jul 1830; R.P. Hastings, More Essays in North Riding History, North Yorkshire County Record Office Publications 34 (1984), 28 and 32. But cf. Mitchelson's less favourable comments as to the workhouse in Hunmanby in the East Riding. N. Mitchelson, The Old Poor Law in East Yorkshire, East Yorkshire Local History Series 2 (Beverley, 1953), 14.

27 Mitchelson, The Old Poor Law, 15.

28 Snell, Annals of the labouring poor, 104-111; J. Ayer, Survey of Pocklington, (Pocklington, 1824).

29 Around 1783/5 it was said to be £117 and in 1803 £237, which was about the level of general inflation over that period

30 See Blaug, ‘Myth of the Old Poor Law’, 178-9. Blaug lists the North and East Ridings as Speenhamland counties but this was probably not so. See Hastings, Poverty and the Poor Law, 11. Expenditure at Market Weighton, probably paying more per head of population in poor relief than Pocklington, appears to have risen from £0.26 per head in 1802 to around £0.65 per head in 1819. (PP Abstract, (1803-4).

31 On the importance of such traditions, see 'Pro Bono Publico, Review of Putman R Det al Making Democracy Work – Civic traditions in modern Italy (Princeton, 1993)', The Economist (UK edition) (6 February 1993), 110.

|