|

The Story of Wilberfoss, its Ancient Priory

and Newton-on-Derwent

by George Beedham, Stamford Bridge.

Wilberfoss undoubtedly got its name in Saxon times from the fact of its being situated on the Foss, or stream, which was the home of the wild boar. A strong beck, taking its rise at Garrowby and Bishop Wilton, runs through it. Between Wilberfoss and Fangfoss is a tract of low-lying land naturally favourable to the rooting propensities of the wild-boar. The Garrowby beck and the Bishop Wilton beck, forming two fangs, meet at Fangfoss and send their united waters to Wilberfoss. Wilberfoss undoubtedly got its name in Saxon times from the fact of its being situated on the Foss, or stream, which was the home of the wild boar. A strong beck, taking its rise at Garrowby and Bishop Wilton, runs through it. Between Wilberfoss and Fangfoss is a tract of low-lying land naturally favourable to the rooting propensities of the wild-boar. The Garrowby beck and the Bishop Wilton beck, forming two fangs, meet at Fangfoss and send their united waters to Wilberfoss.

The road from Wilberfoss to Fangfoss is called "The Storking Lane," evidently once the home of the long-legged wading stork, when much of the land was under water.

With the exception of a tannery that existed at Wilberfoss about a century ago, we have no record of its having been a place of commercial importance.

The York and Hull road passes through the village. It was on this road that John Leland passed from York a little after 1539, for the purpose of antiquarian and topographical research. His description of it is worth repeating. (The words and letters which are inserted in brackets are added to make clear the quaint old spelling, etc.)

"From York to Kexby 'Bridge by Champaine (flat country) meateiy (moderately) fertile v miles.

"This Bridge of 3 fair arches of stone standeth on the praty river of Darwent that cummith by Malton and as I guesse this bridge is toward the middle way betwixt Malton and wher about Darwent goith yuto (unto) Ouse.

"Bridges upon Darwent above Kexby:—Stamford Bridge 2 miles of (off); Buttercrambe Bridge a mile (further); Ouseham bridge 2 miles of (off—still further); Kirkham 2 miles or more (beyond Howsham); Aiton bridge 2 miles (beyond Kirkham); and two

miles to the Hed, Malton...... Yeadinga (Yeddingham) 7 miles (beyond Malton); Aybridge 3 miles (further still).

"Bridges on Darwent byneath Kexby, &c., none, but one use to passe over by feries, saving only Sutton bridg of stone 2 miles lower than Kexby.

"From Kexby to Wilberford village a mile and a dim (half). Wher was a Priory of Nunnes; and on the left-hand was Catton Parke sumtyme the Percy's (i.e. Dukes of Northumberland) now the kinges (Henry the Eighth's).

"Thens to "Barneby Village 3 miles and thens to Hayton village 3 miles, wher is a praty Broke rising a mile of, yn in the Hilles and passith to Darwent as I hard (heard).

"But or (before) I cume to Hayton I passed over Pocklington beck leaving Pokelington about a mile of on the left hand.

"Thens to Thorpe village a mile,

"Thens to Shipton village a mile,

"Thens to Wighton a great uplandish village a mile.

"Thens to Santon village wher Mr. Langdale dwellith 2 miles,

"Then to Lekenfeld vi miles.

"An(d) al this way betwixt York and the Parke of Lekenfield ys meately (moderately) fruitful of Corn and grass, but it hath litl wood."

Catton Park, mentioned by Leland, now owned by Lord Leconfield, and occupied by Messrs. Richardson Bros., was anciently stocked with deer. So many had to be taken out of it yearly to supply Leconfield Castle as it appears from the Household Book of an ancient Earl of Northumberland. Katherine, duchess of Northumberland, as appears from her will proved 9th Nov., 1542, had a residence at Wilberfoss. An extract runs thus:—"I give to my gentlewomen and every one of my household servauntes in wages as well, that quarter's wages; that please God to call me to his mercie, as the quarter's wages next after, with everyone of them hole yere lyverais, with mete and drink for the said quarter, to be taken at my house of Wilberfosse. And also I bequeath unto my saide gentlewomen, ther horses they ride on, with ther saddles and trappers to the same belonging."

This house 'must have been of some pretensions. Presumption puts it in a field between Catton Park farmhouse and Wilberfoss where indications of it were seemingly found.

The Wilberfoss family and former owners of the parish had lived there for many generations. There is extant a complete genealogy of them from Saxon days to the present time. Sir Wm. Dugdale in 1665 shows three generations. Roger, aged 8, and his father, Roger, aged 31. This last Roger's father died in 1662. His wife was Margaret, daughter of John Agar, of Brockfield. The last Mr. Agar died only a few years since.

From Richard St. George's Visitation made in 1612, we find the last-named Roger was then aged 16; that his father, Robert, was lord of Wilberfoss, but for some reason he could not sign his name to his pedigree ;and attested it with a cross. This Robert's father was living in 1584. His wife. Margaret, was the daughter of Andrew Walgatt, of Bishop Wilton, a family which only died out about 120 years ago.

Robert's father was named William. He married Margaret, the daughter of George Overend, Esq., of Kexby, a family which subsequently became the owners of Fangfoss. They built the Hall there in 1777, and died out about 100 years ago.

William's father was named Christopher. He made his will on February 12th, 1533, which is very interesting, showing that beyond his land a country Esquire of that day possessed very little personal property. There can hardly be a doubt that his father built the present Manor House which accords well with the period about 1500. The letters W.W. in. iron are at the end of it. There is some fine old wains-cotting in the inside. A few extracts from Christopher Wilberfoss's will can hardly fail to be of interest:

"My body to be buried within the Kirke of Saint John the Baptist in Wilberfoss; to my Lady Prioresse of Wilberfoss 6s. 8d.; to her sisters 3s. 4d.; to the mending of the organ for the maintaining of God's service 3s. 4d.; to Wm. Wilberfoss, my son, a counter, my greatest brasse pot, a Flanders Chest, a cistern of lead, and a pair of malt querns (mills), also a dunned horse, four years old, and he to give my son Henry 6s. 8d.; to Roger, my son, my second greatest brasse pot, with my best horse, saddle and bridle, sword and buckler, and he to give Edward, Thomas, and Dorothy, my childer, 6s. 8d. each; my son and heir to give yearly to my sister Margaret for life for her cattle one load of hay. To Elizabeth, my daughter, one cowe, my best whie (heifer), 2 young cattle, 5 yowes, and 5 lambs, two mattresses and all that belongs to two beds, and a horse; to Anne, my wife, a nag filly and £40 in money (equal to £400 now), to be paid by my heirs out of my lands at Wilberfosis in equal portions for the space of 6 years."

Several other similar legacies appear in the Will which was proved 18th July, 1534.

After Sir William Dugdale's Visitation at Pocklington on September 7th, 1665, the family remained at Wilberfoss till about 1720, when the estate was sold. One of them went to Hull and married Sir John Lister's daughter, an opulent merchant, and became the ancestor of William Wilberforce, the great slave abolitionist, about whom every schoolboy knows. His son became Bishop of Oxford, and members of the family still hold high positions in the Church.

Sir John Lister's house became the home of the Wilberfosses, and the ancient building in Scale Lane, Hull, is now occupied by the Corporation for the Wilberforce Museum. The family name was very wrongly changed when they got to Hull to Wilberforce, without a shadow of reason. The old spelling is far better for derivative, euphonic, and historic reasons.

The Church of Wilberfoss is not so old as might be supposed, and is no doubt built on the site of a still older one. We can safely assume that we owe most of the present structure to the piety of the Wilberfoss family. There was formerly attached thereto a Chapel at Newton-on-Derwent. This is proved by the will of Robert de Hoton, lord of Newton, made March 15th, 1446, which runs thus:—"To be buried in the aisle of my Parish Church of Wilberfoss, newly built; and I leave 13s. 4d. for purchasing a vestment for the Chapel of Newton; another 13s. 4d. for a vestment for the Church of Sutton-on-Derwent." Several other bequests follow. A brass tablet with effigies of himself and wife are on the floor of the aisle of Wilberfoss Church.

Robert Hutton's family seem to have died out or left Newton, for when Robert Glover made his Visitation in 1584, he found "William Barton, the esquire, there with a daughter, Margaret, aged 10. William's father was named Conan, and his grandfather of Newton, bore the same name, taking us back to about the year 1500.

The Will of Thomas Nykson, of Wilberfoss, made April 1st, 1461, provided for the building of the Church tower, which Will is short and can be quoted in full. "To be buried in my Parish Church, near the grave of Robert Hoton. I will that my executors build, or cause to be built, a bell tower of stone at the western end of the Church to the height of 17 ells under the battlement, provided the parishioners do the carriage, or cause it to be done."

All his property was left for the purpose of building the bell tower, and could his soul visit the scene to-day, it would be gladdened by the mdern piety, which so carefully restored the Church in 1868-9.

Now let us tell the Story of the Benedictine Priory of Saint Mary of Wilberfoss. It is surprising what a large amount of information is extant respecting the institutions of our forefathers round Pocklington. But little of this interesting matter is however really known to the inhabitants of the district. In giving an account of the priory, its foundation, its possessions, rents, etc., we shall be taking a retrospective view of the lives and social condition of our forefathers four and five hundred years ago, Further, it is hoped, it may intensify that pleasant mental halo ever surrounding the acts, deeds, and movements of our ancestors.

Before proceeding further we will give a brief account of the monasteries generally, their origin and intention. Some of them were called Abbeys; some, Priories. The former were of a rank superior to the latter, and had various privileges of a higher order. The ruler of an Abbey was called an Abbot or an Abbess; of a Priory a Prior or Prioress. There were different orders of the Monks and Nuns, who had different rules for their government, and mode of life, and were distinguished by different dresses. Some orders were more severe in discipline than others. The Cistercians for instance were far more strict and austere than the Benedictines. The former have been styled by some the Revivalists, by others the Quakers of the Middle Ages. Posterity will be ever indebted to them for the numerous arts, sciences by them bequeathed to it.

The persons belonging to a Monastery lived in common in the same building. They could possess no individual property; when they entered the monastic life they left the world behind them; they took a solemn vow of celibacy; they could will nothing away; each possessed a life interest, but nothing more, in the revenues of the body; and the business of the whole community was to say continual prayers, and particularly to do acts of hospitality and charity in the neighbourhood of their respective houses.

This mode of life began by single persons separating themselves from the rest of the world and living in complete solitude, passing all their days in prayer and dedicating themselves wholly to the service of God. They were styled "hermits," and their conduct drew towards them great respect. As time wore on, such men, or men of like propensities, formed themselves into societies, agreed to live together and to possess things in common. Women did the same. In this manner rose the monasteries. The piety, the austerities, and particularly the works of kindness and of charity performed by these persons made them objects of great veneration: and the rich made them in time the channels of their benevolence to the poor. Kings, Queens, Princes, Princesses, Nobles, and Gentlemen founded monasteries: that is to say, erected the buildings and endowed them with estates for their maintenance. Others from a pious disposition or by Way of atonement for their sins, gave while alive, or bequeathed at their death, lands, houses, and money to monasteries already erected. So that in time the monasteries became the owners of great landed estates; they had the lordship over innumerable manors and had a tenantry of great extent, especially in England, where the monastic orders were ever held in great esteem in consequence of Christianity having been re-introduced into England by Saint Augustine and a community of Monks.

Saint Anthony, in Egypt, is said to have been the first Christian hermit, who retired from the world to the desert in the second or third century of our aera. The Scriptural authority for this ascetic mode of life seems to be the Counsel given by the Saviour to the young man of great wealth in order to enable him to obtain the perfection of godliness: "If thou wilt be perfect, go sell all that thou hast and give to the poor and thou shalt have treasure in heaven." (St. Matt., xix, 21.)

It will thus be seen that the sons and daughters pf the wealthy, or those who had something substantial to lose in the shape of earthly property, could really fulfil the Counsels of perfection. Elijah, the prophet, and Saint John the Baptist seem to have been hermits in nearly all senses of the word.

The Nuns of Wilberfoss were of the Benedictine order, that is followers of the rule of Saint Benedict, who was born of a wealthy family at Nursia in Italy in 480 AD and died 543 AD. It is pleasant to know that his rule, besides inculcating religious exercises, directs that the Monks shall employ themselves in manual labour and also impart instruction to youth.

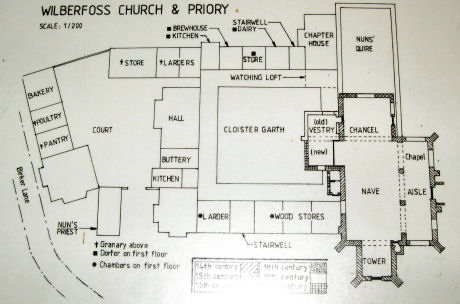

The Nunnery stood near the Parish Church, and had at the dissolution a Prioress and twelve Nuns. The building included a church, the choir containing 16 stalls and three altars. The Parish Church adjoined that of the Priory: there was a cloister in the north side 60 feet square, the alleys being 6 ft. wide, but unglazed; on the east the Chapter house 23 feet long and 16 broad, with dormitory above; and on the north and west the hall and various other offices. No remains now exist. The writer believes it to have been of wood, as no stones are visible round about and built into the modern houses. The Nuns had a water mill probably close by. If so it could only have been worked by a breast wheel, the fall being insufficient for ;an overshot one.

The Nuns were never at any time possessed of a large revenue, but we may rest assured that on the whole, they acted faithfully to their trust. We have seen that Christopher Wilberfoss left the prioress 6s. 8d.and the sisters 3s. 4d. just before the dissolution. Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, left them ten pounds in 1489. If wickedness and misrule had been the character of the Nuns, we may be certain they would not have done it. Moreover it speaks volumes for the character of the monastics, that the country gentry in their Wills, generally left modest sums of money to the monastery near to which they lived. Of course it would be vain to say that no objection could be taken to the monastic life, or that the monastics themselves were at all times and in all ways perfect. But when abuses and misrule did arise, there were ways and means for correcting them.

Every institution under heaven is liable to some objection or fault. Even the very waggons that bring the harvest home kick up a bit of dust in one's face. Let us not then judge of the monasteries harshly, or be led away by prejudice purposely created by persons interested in defaming them. The writer himself was up to his twenty-fifth, year, by reason of the false statements inculcated in his youth, about as prejudiced against them as he well could be. But getting to London, and getting access to the great libraries there where "he could see the original documents and letters written by the men who were instrumental in destroying and spoiling them, he saw only too clearly the real motives of Henry VIII. and his unrighteous gang, who stole the property of the poor in the most nefarious manner.

Henry had no idea that his letters would be open to inspection in the 19th Century, and his wickedness and hypocrisy seen through. Even poor Anne Boyeyn never thought that her famous (infamous?) letter to Henry from Hever Castle would be extant now and besmirch her character beyond redemption! Sixty years ago, imposters came about the country lecturing about the horrid deeds that were done in Nunneries: and even to-day certain people believe as an article of faith, the "Awful disclosures" of Maria Monk, another impostor, who pretended to have escaped from a Nunnery in Montreal in 1835. and whose lying statements have been fully disproved. But the book for all that must have been a mine of ill-gotten, wealth to Maria.

When the reader sees the Nuns of York going about on their errands of mercy to-day, with faces radiant with that happiness that ever comes of doing good and charitable deeds, let him judge for himself whether Nunneries are abodes of iniquity. The writer solemnly declares he has never seen an unhappy looking Nun. during the whole of his long life.

It must not be 'forgotten that Henry the Eighth's Commissioners of Enquiry before the Dissolution were specially chosen (Drs. Leigh, London, and Layton, to wit) for their impudence, effrontery and ability to cone act the foulest lies and scandals, in order to trump up. a pretext for the seizure of the monastic property by the most lying, most blood-thirsty, most hypocritical, and most unscrupulous tyrant that ever disgraced the pages of History. Their reports are extant, and of course are very awful—too awful for the impartial and judicial mind to swallow. That the accused were not allowed to answer in defence or contradict, is quite enough to show what they are worth.

It requires no great mental stretch to look back and view the pious sisters of Wilberfoss, daughters of the neighbouring gentry, fulfilling their mission of charity to the inhabitants of the district, during their four hundred years of office. The very earth of our churchyards, feet deep, is made up of the bodies of men, women, and children — the accumulation of over a thousand years. Could that earth be re-vitalized in human form, a great deal of it would without doubt testify on their innumerable deeds of charity, goodness and excellent works. Imagination easily pictures them receiving the title-deeds and evidences of property, and even the money of the people of the neighbourhood, to be by them retained in safe custody; it views them teaching the children of these same people to read English (sometimes Latin), grammar, and Church music without expense; it views them teaching young women how to perform domestic work to the best advantage; it views them carefully nursing and rearing the fatherless and motherless orphan; it views them relieving the needy and the halt, the sick and the unfortunate, as well with bread, as with spiritual advice and religious consolation. There were no workhouses in those days, and the Priory stood to the poor in its stead. It was to them as a green oasis to the weary traveller in the desert — a kind of land of Groschen flowing with bountiful hospitality, and enjoying its own light and calm amidst darkness and storm around.

The Monastics generally were without doubt easy and good landlords, with a tenantry that never left the estate for generations. Such a fixedness was ever the friend of rectitude in morals, and conduced immensely to prosperity, private and public. The Monastery was a proprietor that never died; its lands, mills, and houses seldom changed owners; its tenants were liable to none of the uncertainties that other tenants were; its timber had never to tremble at the axe of a betting, gambling, and squandering heir. In passing let it be stated that no owner of land who bets should, in the public interest, be allowed to retain it, any more than a commercial clerk who does so, be allowed to handle his master's money. Experience shows that such a person cannot for long keep his hands off it.

The monastics were ever renowned for letting their land at moderate rents, quite a different thing from the modern farmer who, when he becomes a landlord, generally exacts about double to that which he paid himself; who does as little as he can by way of repairs or improvements; and who when asked to put things in order has usually this sterotyped answer: "It will last my time."

Wilberfoss Priory was founded before the year 1153, and possibly about fifty years after the Norman Conquest in 1066. Henry II., who reigned from 1154 to 1189, confirmed its rights by Charter, which is still extant. According to Leland the founder was Alan, the son of Helias de Catton, who gave to the Nuns all the land belonging to one fee with a meadow at Catton-upon-Derwent. Fees varied in size, according to quality of land; we compute this gift to have been about 40 acres. The brief Charter in Leland's Collectanea is evidently only an abridgement of the original, for George Duke of Clarence, who was patron of the Nunnery in the reign of Edward IV. (1461-1483), in a Charter of inspection and confirmation, recapitulates Alan's Charter more at length, and states that Alan in addition to the fee and the meadow above-mentioned, gave also his hall, a toft and two copses to the Nuns. Alan's mansion seemingly stood in the Sector's garth in front of the Derwent at Low Catton; and it is interesting to note that the "Nun's Ings" are still mentioned on the charity boards of the Parish Church.

King Henry II. (1154-1189) confirmed to the Nuns the Chapel of Weiton (Market Weighton) .... also Jordan the son of Gilbert's donation of the Church of "Wilberfoss, as well as a bovate of land with tofts (cottages) in the same village, given by William, the son of Robert de Wilberfoss.

King Henry III. (1216-72) in the twelfth year of his reign confirmed to the Nuns nine acres of land in Meltonby, given by Robert the son of Ernisius de Melthaneby with a Croft; two bovates of land in Yapham, given by Simon Archer, the vassal of John le Poer; two bovates given by Matilda the daughter of Alan, in Youlthorpe; two other bovates in Yapham given by Simon Archer; two cultures of land in Wilberfoss with certain houses and a mill, given by Matilda, the daughter of Alan de Catherton (Catton), and four of land in Youlthorpe, given by Robert de Neuby and John the son of Ivo, and their wives, with the corpise of Thomas Arundel of Youlthorpe. This means they agreed to give Thomas Arundel the right of burial in the monastic church of Wilberfoss.

In 1239 the Nuns had half a carncato of land with pasturage for 100 sheep in Givendale. Likewise lands and a meadow in Cave. Anya de Percy gave them an oxgang with tofts and crafts in Easthorpe. Peter de Rotherfield, son and heir of Eufemia de Lisle, wife of Nicholas de Rotherfield, in 1291 quit claimed all his right in two oxgangs of land in Newton-on-Derwent, which the said Eufemia, his mother, had given. The Nuns had tenements in Seamer Juxta, Irton near Scarbro, and lands "in Sutton-on-Derwent. William de Gurnays or Gunese, and Thomas, son of Robert de Boulton, near Fangfoss, gave two oxgangs of land in Yapham, of the fee of Sir Robert de Grey, Knight, who exempted the Nuns from doing foreign service, or suits of Court, or other secular service for the same. Robert de Boulton also gave an oxgang of land in Yapham. This Robert de Boulton was certified lord of Boulton, and also of Appleton in Ryedale in 1316. Thomas de Boulton, son and heir of Robert, brother and heir of John de Boulton, held the manor of Sutton-on-Derwent' in 1300 and 1316. The family later became very influential as merchants in York. Their hall at Bolton stood with its moats in a field now owned by Mr. William Sampson. In 1584 the owner of the Bolton estate was William Micklefield. The family had held it for three generations previously, at least.

We have spoken of land in Carucates, Bovates, and Oxgangs. Carucates was as much land as one plough could cultivate in a year, usually about 40 acres. Bovate and Oxgang mean the same thing, as much as "would keep an ox for a year, usually about four acres. A Knight's fee was about 50 acres, more or less according to quality of land; oxgangs and bovates also varied for the same reasons.

But very few names of the Prioresses of Wilberfoss are extant. The following are all that are known:— Christina occurs, prioress in 1235; Emma de Wallcrimgham resigned in August, 1310; when Margaret de Altaripa was elected. At this time there were 19 Nuns in the Priory. Another election of a Prioress appears to have taken place in April, 1319. The name of De Altaripa is interesting. The family were resident at Full Sutton down to about 200 years ago, by which time their name had got corrupted into Dealtry, Dealtrey, Daltery, Dawtrey, or Dautre. The family gave Rectors and Vicars to several parishes around, including Westow, Skirpenbeck, Full Sutton, Bishop Wilton, and Catton. Their Latin name meaning "High Bank," probably took its name from the fact of their once having dwelt on the edge of the Wolds near Malton, The family were at Full Sutton for hundreds of years, for in 1279 Ralph de Altaripa presented the living of Full Sutton to Ralph -de Cawood. Their latest mansion still exists as the Manor House, now occupied by Mr. Arthur Leo Mennell.

After Margaret de Altaripa's term of office, the names of successive Prioresses are lost for nearly a Century, when Eleanor Daykyrs was complained of for mismanagement in 1409. Anne Kirkby was confirmed Prioress July 31st, 1475. She resigned October 10th, 1479. Margaret Esyngwold was made Prioress December 6th, 1479. She died in 1512, and was buried in front of the pulpit of Pocklington Church. Eliza Lorde was confirmed Prioress October 18th, 1512. She was the last Prioress, and died in 1550, having survived the Dissolution in 1539 about 11 years. She doubtless received a small pension like some of her other sisters, for we find that in 1553 some of the Nuns were still living and drawing the following annuities:—Agnes Burton, 33s. 4d.; Alice Metcalfe, 26s. 8d.; Joanna Andrew, 26s. 8d.; Alice Thornton, 20s.; Beatrice Hargall, 26s. 8d.; Isabella Creake, 26s. 8d.; and Margaret Brown, 26s. 8d. Multiply by ten and the pensions will be fairly estimiated in modern money.

In ancient times when neither Banks nor Insurance Companies obtained, it was the custom of wealthy people when they wished to provide for an old servant, friend, or anyone else, to give a substantial sum in either land or money to a monastery to purchase a corrody. This was a right to maintenance for life by the person on whose behalf it was purchased. One fortunate man of this class, Edward Harlings, existed in 1553, and drew an annuity of 59s., in lieu of the right of which he had been deprived by the Dissolution of the Minor Monastery of Wilberfoss.

When Henry the Third confirmed the gifts to the nunnery about 1228, the title deed states thus:—

"Ofthe gift of Miatilda de Catherton (i.e. Catton) the whole culture of land in Wilberfoss, which is called Milncholm with the houses thereon erected; also a mill with a pond (molendinum cum stagno) in the same township. And another piece of tilled land in the same village, called Milneholm Hevethlands as far as is contained in length and breadth from the ditch right up to the Common road of Seneker."

There was hardly a monastery in England that did not own a water-mill: and the present inhabitants of Wilberfoss may possibly identify the sites of the above properties.

The Charters of the Nuns were examined and confirmed by George Duke of Clarence between 1461 and 1483. This man was no other than the "false, fleeting, perjured Clarence" of Shakespeare. He was drowned in a butt of Malmsey wine in the Tower of London by his "brother Edward the Fourth. He was the son of Richard Duke of York, whose head with a paper crown thereon, was stuck on a pike atop of Micklegate Bar, York, after the battle of Wakefield in 1461, by order of Margaret of Anjou,. whom the great dramatist makes to say "off with his head, and set it on York gates; so York may overlook the town of York." Every schoolboy has read Clarence's dream in the Tower, and shuddered at the description'of the mental agony endured by the wretched man — a fortaste of hell itself.

"With that methought, a legion of foul fiends Environ'd me and howled in mine ears Such hideous cries, that with the very noise, I, trembling, wak'd, and, for a season after, Could not believe but that I was in hell."

The Priory of Wilberfoss was dissolved on the 20th of August, 1539. The Dissolution was brought about in this wise. Henry VII. died in April, 1509. His natural propensity was avarice; and he spared no means to get money, fair or foul. He had two rapacious ministers, perfectly qualified for the job. Both were lawyers: the first of mean birth, brutal manners, and "unrelenting temper; the second better born but equally unjust.They were made Barons of the ExChequer and thus were able to practice the most iniquitous extortions under legal pretences. Spies, informers, and inquisitors were rewarded and encouraged in every part of the kingdom. By these means Henry VII. got £1,800,000 in hard cash, equal to 18 million pounds to-day. Scamps usually breed scamps, and thus his son Henry VIII. was an out and out spendthrift. Before the year 1536 he was downright hard up. We all know how he had in the meantime divorced himself from Queen Catherine and broken her heart; how he had quarrelled with the Pope about this divorce; and how he had self-constituted himself the ruler of people's consciences by making himself supreme head in matters of religion. He had murdered the good Sir Thomas More, the venerable and beloved Bishop Fisher, and other good people because they conscientiously disbelieved the impudent claim, and had the courage of their opinions to contradict it. Strange anomaly—a tyrant without a conscience usurping the right to regulate those who possessed that Godfearing principle! John Houghton, of the Charterhouse Priory in London, was one who refused to admit the vile principle and preferred the most horrible of deaths. He was dragged to Tyburn, four miles on a hurdle. Scarcely suspended the rope was cut and lie fell alive to the ground. His bowels were torn out; his heart was ripped from his body and flung into a fire; his head was cut from his body; that body was divided into quarters and half-boiled; the quarters were then sub-divided, and hung up in different parts of the City of London; and one arm was nailed to the wall over the entrance into the monastery.

Henry had thus by means of the rack, the gibbet, and the executioner's axe got both his subjects and his parliament into "the most abject servility. In the year 1528 an Act had been passed to exempt the King from paying back any sum of money that he might have borrowed; another Act followed this for a similar purpose, and great numbers were ruined. To complete a series of tyrannical acts such as were never before heard of, it was enacted in 1537 that except in cases of mere private right "the King's Proclamation should be of the same force as Acts of Parliament." Thus, then, all law and justice were laid prostrate at the feet of a single man, and that man with whom law was a mockery; on whom the name of justice was a libel; and to whom mercy was wholly unknown.

In destitute circumstances, Henry determined to confiscate the lesser monasteries. No doubt he thought the greater and richer ones would be too hard a nut to crack. When men have the power to commit and are resolved to commit, acts of injustice they are never at a loss for pretences, and Henry soon found them. Before doing so, and in order to set all law at defiance, to rob the poor and helpless, to deface the beauty of the country and make it a heap of ruins, he required a suitable agent. The tyrant found him in Thomas Cromwell, whom he appointed to be "Royal Vicegerent and Vicar General," or right-hand man in executing his unholy will. He was the son of a Putney blacksmith and became an underling in Cardinal Wolsey's household, where he attracted the attention of the King, who quickly advanced him from post to post. He was made a Peer, and took precedence over every other man save the King, He was an upstart ruffian, and disposed after the King's own heart; and like him a tyrant and a coward. John Stow, the historian, of London, says he had a house near the present Bank of England; that he took his neighbour's garden wall down, and put the land to his own. The poor fellow thought his life of more =value than the garden, and dare not say a word. Henry VIII. could not bear to see a funeral in his last years; and no low-bred criminal ever staggered to the gallows with such a craven heart as that possessed by Cromwell. When in 1540 he had answered the tyrant's purpose and obtained thirty estates out of the monastic plunder, he very properly reaped the benefit of his own way of administering justice.

It was not expedient to leave him so well off: he was arrested on a trumpery charge and beheaded. Before his death he was so complete a coward, that he wrote the most disgusting letters to the King, begging for his life in the most slavish and base manner; compared his smiles and frowns to those of God; besought him thus:—"To kiss his balmy hand once more that the fragrance thereof might make him fit for heaven." The dastardly caitiff also wrote:—"I, a most woeful prisoner am ready to submit to death when it shall please God and your Majesty; and yet the frail flesh incites me to call to your grace for mercy and pardon of mine offences. Written at the Tower with the heavy heart and trembling hand of your Highnesses's most miserable prisoner and poor slave, Thomas Cromwell. Most gracious Prince, I cry for mercy, mercy, mercy."

The reader will easily judge whether such a cowardly miscreant was fit to live.

In order to set to work, Cromwell set on foot a Visitation of the Monasteries, assisted by deputies of the basest character (Doctors Leigh, London, and Layton to wit). Impudence, effrontery, and ability to concoct the foulest lies were the necessary character of these men. The object was to obtain grounds of accusation; and the deputies wrote in their report, not what was, but what their employer wanted them to write. The accused parties had no means of making a defence. They dared not complain, or offer any. They had seen the terrible deaths of their brethren, who dared to dissert from any dogma or decree of the Tyrant. The reports thus obtained were embodied in a work called the Black Book. On the mere surface of them, so evidently untrue are they, that no modern Court of Justice would countenance them for one brief hour! They answered their purpose, and an Act was passed in March, 1536, confiscating to the King the 376 lesser Monasteries, or those with incomes less than £200 a year. Slavish and full, as the Parliament was, of men greedy and hopeful to get plunder, the Bill, Sir Henry Spelman says, stack a long time in the Lower House, and could get no passage, when the King commanded the Commons to attend him in the forenoon in his gallery, where he let them wait till late in the afternoon, and then coming out of his Chamber, walking a turn or two amongst them, and looking angrily on them, first on one side and then on the other, at last he said: "I hear that my Bill will not pass; but I will have it pass, or I will have some of your heads." This constitutional argument was quite' enough; the Bill passed.

As the preamble to this Act is without parallel in History as the most shameless piece of hypocrisy that was ever committed to paper, we will give it in full:—

"For as much as manifest synne, vicious, carnal, and abominable living is dayly used and committed, commonly in such little and small Abbeys, Priories, and other Religlous Houses of Monks, Canons, and Nuns, where the congregation of such Religious persons is under the number of twelve persons, whereby the Governors of such Religious Houses and their Convent, spoyle, destroye, consume, and utterly waste, as well their Churches, Monasteries, Priories, Principal Farms, Granges, Lands, Tenements, and Hereditaments, as the ornaments of their Churches and their Goods and Chattels, to the High Displeasure of Almighty God, slander of good religion, and to the great infamy of the King's Highness and the Realm, if Redress should not be had thereof. And albeit that many continual Visitations hath been heretofore had, by the space of two hundred years and more, for an honest charitable Reformation of such unthrifty, carnal, and abominable living, yet nevertheless, little or no amendment is hitherto had, but their vicious living shamelessly increaseth, and augmenteth, and by a cursed custom so rooted and infected, that a great multitude of the Religious Persons in such small Houses as rather choose to rove abroad in apostacy than to conform themselves to the observation of good religion; so that without such small Houses be utterly suppressed and the Religious persons therein be committed to great and honourable Monasteries of Religion in this Realm, where they may be compelled to live religiously for Reformation of their Lives, the same else be no redress or Reformation in that behalf. In consideration whereof, the King's most Royal Majesty, being Supreme Head on Earth, under God of the Church of England, dayly studying and devysing the Increase, advancement and Exultation of true Doctrine and Virtue in the said Church, to the only Glory and Honour of God and the total extirpation and destruction of Vice and Sin, having knowledge that the Premises be true, as well as the accompts of the late Visitation, as by sundry credible Informations; considering also, that divers and great solemn monasteries of this Realm wherein (Thanks be to God) Religion is right well kept and observed, be destitute of such full number of Religious Persons as they ought, and may keep, hath thought good that a plain Declaration be made of the premises, as well to the Lorde Spiritual and Temporal, as to other his loving Subject, the Commons in this present Parliament assembled. (Please reader note well the statements in the above long sentence). Whereupon the said Lords and Commons by a great deliberation finally be resolved, that it is, and shall be, much more to the pleasure of Almighty God, and for the honour of this his realm, that the possessions of such Religious Houses now being spent, spoiled, and wasted, for increase and maintenance of sin, should be used and committed to better uses, and the unthrifty Religious Person in spending the same to be compelled to reform their lives."

The above is without doubt the most lying, hypocritical, and plasphemous document, ever drawn up by the hand of man on earth!

The preamble shows clearly that Henry had then no intention of attacking the larger monasteries. They were perfection, and continued so for only a brief while, till he again got hard up. The reader will see that the charges against the small monasteries were loose and general, and levelled against all Religious Houses whose revenue did not exceed a certain sum. This alone was sufficient to show that the charges were false; for who will believe, or can believe, that the alleged wickedness extended to all whose revenues did not exceed a certain sum, and that when those revenues got above that point, the wickedness stopped! Nearly three years elapsed before all the Lesser Monasteries and their property were dealt with in detail. But the nefarious work went on, not without opposition. A rising of the people took place in Lincolnshire, which was put down without much difficulty. A more formidable insurrection followed in Yorkshire, styled "The Pilgrimage of Grace." It was headed by a gentleman named Robert Aske, of Aughton, and was composed of no fewer than 40,000 men. York, Hull, and Pomfret Castle were all taken, and it seemed at one time all over for Henry. But his letters show that, like the present German Emperor, he was a master hand at lying and treachery. Aske was in every sense a man of honour and principle, which was his ruin. He put faith in Henry's promises, which really were not worth a rotten nut, disbanded his followers, and then, alas! the Tyrant seized his person and had him hanged as a traitor in tho Pavement, York!

The goods, chattels, and plate of the Lesser Monasteries brought in £100,000 to the privy purse of Henry—equal to a million now; and the estates showed a revenue of £32,000 a year, equal to £320,000 now.

Great promises had been held out that the King, when in possession of the estate,-; of the Lesser Monasteries, would never more want taxes from the people. But he soon found out that he could not keep all the plunder to himself. Hungry agents called for a share: they knew he had good things; and he knew that it was policy to let them have a portion, or his supporters might leave him some day. Before four years were over he found himself as poor as if ho had not stolen a single convent. Seeing that his first Confiscation Act of 1536, had declared the Greater Monasteries to be well conducted and free from all corruption whatsoever, it seemed a work of some difficulty, in so short a time especially, to find reasons for the confiscation of them. But tyranny stands in need of no reasons. Cromwell and his party beset the needs of the Great Establishments; they threatened; they promised; they lied and they bullied. By means the most base, they obtained from a few what they called a "Voluntary surrender!" If they were met by sturdy opposition they resorted to false accusations. and procured the murder of the parties under the pretence of having committed high treason. It was under this infamous pretence that the Abbots of the famous Abbeys of Glastonbury, Newstead, Reading, Colchester and many more were hanged and ripped up ignominiously. So that the surrender, wherever it did take place, was of the nature of those voluntary surrenders one makes of one's money when a highwayman's pistol is pointed at one's head. But "Voluntary Surrender" was too troublesome and too slow for Henry, Cromwell, and other Cormorants waiting for the plunder. Without more ceremony, an act was passed in the 31st year of Henry VIII. giving the surrendered and all other monasteries to the King, his heirs and assigns. Never before or since has there been such a rich harvest of pillage. They tore down the altars to get away the gold and silver, ransacked the chests and drawers, and tore off the covers of books, that were ornamented with precious metals. Most of them were in manuscript, and single books had taken in many cases a long time to compose or copy. Whole libraries, the getting together of which had taken ages upon ages, and had cost immense sums of money, were scattered, destroyed, and lost for ever.

Hence it is we hardly know the details of the history of our own country before "this period. They gutted, sacked, and destroyed the rich tombs of Saint Augustine and Thomas a Beckett at Canterbury. To the former belongs the honour of being the apostle of England—the introducer of Christianity to our Saxon forefathers. Beckett had resisted a former Henry, named the Second, over three hundred years; before, and had stack up for the libertieis of the people against the Crown, and given his life in their cause. By the Tyrant's special order, who hated the name of Beckett, his ashes were dug up and scattered to the winds, under the personal superintendence of Cromwell. The barbarians spared not even the tomb of one of the greatest Englishmen that ever lived,—the tomb of Alfred the Great, in Hyde Abbey, Winchester, where the very coffins, were dug up and the lead sold. If the tomb of the Saviour of men had been there, and of like pecuniary value, if would not have met with a better fate.

Thus noble buildings raised in the view of lasting for countless ages, were demolished. Gunpowder was used in most instances, and thus the magnificent structures which had required ages on ages to bring to perfection were made heaps of ruins. Their remains are even now the envy of the American people, who with all their immense wealth, have never yet possessed one of the same beauty and magnificence. In many cases thosie wjio got the estates for no merit of their own 'whatever, were bound to destroy the buildings, so that the people should at once be deprived of all hope of ever benefitting by the property again. No one save these vampires was the better for the plunder. The poor were Cruelly deprived of the relief which their forefathers had enjoyed for centuries.

Thus in the end Henry suppressed 645 Monasteries, 90 Colleges, and to cap the whole, 110 Hospitals. The latter "were founded by charitable people for the support of poor, aged, infirm, and unfortunate persons. One at York, St. Leonard's Hospital, whose ruinous Chapel towers above your head near the Museum Gates, had an income of £600 a year, equal to £6,000 now. The whole revenue of the suppressed establishments was £161,000 a year, equal to 16 millions now.

Henry was so poor at the close of his reign, that he instituted another commission for enquiry into the character of the little Chantries. These were Chapels of Ease, founded and endowed in nearly all cases by the parishioners, on account of distance from the Mother Churches. The Commissioners were a better class of local men than those who compiled the Black Book. We have read many times over, and always with pleasure, their report so far as this big County of York is concerned., and can scarcely find a veniality against the Chantry Priests. We have seen immensely greater abuses in the Church of England in our time. To wit, the deeply learned Eev. Thomas Eankin, cur-ate-in-charge of Huggate, a splendid Greek and Latin scholar, a philosopher whose papers were ever welcomed at the meetings of the British Association, starved on £70 a year, and a house, and had to eke out his living by keeping a school. The real holder of the living was Lord de Saumerez, who pocketed more than three-fourths of the income, and it is said never appeared after he read himself in! Similarly the Dean of Ripon held the rich living of Kirby Un-derdale, over £1,000 a year, and coolly stuck to the best jpart ,of it, whilst t.he Rev. Mr. Atkinson conscientiously did the work there for so many long years, but who was cruelly turned out of it when the Rev. Thomas Monson was inducted. This state of things existed all over England, one man often holding several livings. A man of this class, Vicar of Bassingham, Lincolnshire, won the St. Leger at Don-caster less than fifty-two years ,ago!

Notwithstanding the excellent reports generally about the conduct of the Chantry Priests, their endowments were ruthlessly taken from them in 1547 and used to carry on the war with Scotland, and to pension Court favourites! They were nearly all schoolmasters, who taught the people to read and write, hence Henry put the educational clock back 300 years, for pnly 70 years ago the bulk of the people could neither read nor write in London. It was then a regular thing for a man to publicly read the newspaper to them on Clerkenwell Green on Sunday mornings. The Chantries of Boltoii and Youlthorpe were local instances of this unjust pillage.

Nevertheless by reason of the King's (Ed. Vlths) 1 'sore want of money," shortly after another Commission was appointed to rob the Parish Churches! All articles of value, such as vestments and bells (save one), together with the lead off the roofs were gathered together in the East Riding and shipped from Hull to London. The parishioners were impudently told to replace the roofs with boards and thatch I The marvel to-day is that there is a single acre of land left to the Parish Churches. A great number of the latter formerly belonged to Monasteries, who served them With a Priest, a Vicarius (or one in place of another), hence when Henry carried out the Great Pillage he stole the Great Tithes, and either sold them or gave them away to his friends. This is why we so often see them in other hands than the parson's to-day, and this is also why the parsons livings are so often wretchedly small. The mischief can never be undone.

Could the Abbeys and their immense properties have been retained for the benefit of the people at large which they should have been, no one can tell the untold advantages and blessings which the people of England might be reaping to-day. Not one sick, aged, or infirm person of good behaviour, need have been in want. What a jump for joy there would be if the sick could claim sanctuary and recruit their health within the Cloisters of Warter, Fountains, or Rievaux! And what a blush of shame it brings to the cheek of every honest Englishman, to think that the beautiful time-enduring buildings of the 648 Monasteries and their fine estates, in this country, should have been perverted from their pious uses for ever, at the hands of the most unjust, hard-hearted, most mean, and most sanguinary tyrant that the world ever beheld, whether Christian or Heathen!

As a practical illustration of the good that might have been done had the monastic property been retained for charitable purposes, let us look to the small town of Stamford, in Lincolnshire. There "they have about a dozen different hospitals, or almshouses, locally called Callises, because they were founded in Catholic times by merchants of the staple or market of Calais. These men bought up the English wool, shipped it to Calais, where it was sold to the Flemings, who were then the great clothmakers of Europe. How it is that Henry the VIII. never stole them, no one now knows. No doubt some influential Courtier saved them. These "Galiises" at Stamford have been a glory to the town for ages. No one with a decent character seems to fear poverty there.

The general expression of those, who are losing in the battle of life, is: "Well, if the worst comes to the worst I shall get into a 'Callis.' " One of these Callises is for broken-down farmers, founded by a merchant named Brown, some 400 years ago. A descendant, a merchant of New York, came over some years ago, and found the Charity so well administered that he rebuilt the hall and left it a lot more money. The charities given in Protestant days are far behind those of Catholic times. The charity boards in our Churches prove this to the hilt. A number of trumpery paltry gifts are shown thereon, many of which have been lost because they were not worth looking after.

Wilberfoss Priory was doubtless pulled down, and the paterial scattered and sold, for the site, thereof was granted to George Gale, Esq., a rich Goldsmith, of York, in 1553. He had married Elizabeth Lord's sister, the last Prioress, and perhaps bought it out of respect to her. Her brother, Brian Lord, was a merchant at the end of the old Ousebridge, in the Parish of St. Michael, in Spurriergate. He left each Nun in Wilberfoss 6s. 8d., and George Gale and the Lady Prioress were his trustees. His Will runs thus:—

"My Ladye Prioresse to have my best horse, and my brother, George Gale, 20 shillings for their labours. Moreover I will that my sister, the Ladye Prioresse of Wilberfoss, shall have my daughter's Isabell, with her childe's portion of £41 13s. 4d. To my nece Dame Mabel of Wilberfosse, to pray for me, V shillings, etc."

The Common Seal of the Priory was oval, having the Salution of the Virgin Mary in the area, and the letter W below. The inscription round was Sigill see Mariae de Wilberfossa (Seal of St. Mary of Wilberfoss.)

Below are the accounts of the property as settled after the Dissolution, taken from the paper Surveys time of Henry VIII., now in the Augmentation Office.

"Wilberfosse lately a Priory of Nuns in the County of York concerning the revised rent roll of the lands and possessions belonging to the said late Priory, etc.. etc."

"The site of the late Priory and the ecclesiastical lands lately in the hands and occupation of the late Prioress in the same place.

"Henry Whitrasyn, Knight, holds the site of the said late Priory with dovecotes, gardens, orchards, and pleasure grounds, and other conveniences, within the precincts thereof at a rent of 6s. 8d.

"He also holds nine acres of meadow land lying beneath the meadow known as Darwent Ings, and pays a rent of £1 7s. 0d.

"He also "holds one close of pasture land called "Cowe Close," containing by estimation five acres at a rent of 5.s.

"He also holds one close of pasture land called-----,

next the site of the said late Priory, full of trees, and thorns, at a rent of—nothing.

"He also holds two closes of land of which one is called Chapel Garth, and the other Chapel Garth Flat, lying below the open unenclosed fields (campos) of Newton, lately in the holding of William Burden, at a rent of 11s.

"And the aforesaid tenant will further pay the dues of the Chaplain officiating in the Chapel of Newton aforesaid.

"He also holds one wind-mill (molendinmun ventriticum), there lately in the holding of the aforesaid William Burden, at an annual rent of 13s. 4d. Total, £3 3s. 0d.

YOWLETHORPE.

"Thomas. Cooke who holds by indenture under the 'Common Seal of the said late Priory, for a term of years, one tenement with a toft and 16 bovates of land in Yowlethorpe, at an annual rent of twelve quarters of wheat at a price in average years of 5s. 4d. a quarter—£3 4s. 0d.

MELTYNBY.

"Robert Blande, who holds one tenement with a toft croft, .and eight bovates of land in Meltynby, at an annual rent of eight quarters of wheat, estimated at 5s. 4d. a quarter—£2 2s. 8d.

THE RECTORY OF WILBERFOSSE AND NEWTON.

"The aforesaid Henry Whitrasyn holds to farm the Church or Rectory of Wilberfosse, with the tenths of corn and all other lesser tithes and private offerings belonging to the same Rectory at an annual rent of £8 0s. 0d. And the same tenant will further pay the salary of the Curate of the Parish Church.

"The same Henry holds to farm one messuage and four bovates of glebe land, lately in the holding of Elizabeth, widow of Robert Harlynge, at a rent of £1 17s. Od.

"The same Henry holds 10 acres of low fenland there, with ten of hempe and flax, lately in the holding of Wm. Dennys at a rent of 6s. The same Henry holds another messuage and three bovates of glebe land, lately in the holding of William Pereson, at a rent of £1 14s. 0d. Total, £20 6s. 8d."

The above does not include all the property of the Convent-—only that portion attached to the Church and Rectory.

"From the account of Ralph Beckwith collector, etc., in the 33rd year of Henry VIII. the rents and dues from the parishes of Wilberfoss, Newton, Catton, Helperthorpe, Givendale, Ousethorpe, Seamer, South Cave, Morley, Sutton-on-Derwent, Youlthorpe, Meltonby, Weighton, Pickering, and Stamford Bridge; the total shows the Priory had a total rent of £39 15s. 9d. Thus the whole income in modern money (exclusive of continual gifts) would be say £400 a year.

To illustrate fully the period of the Dissolution we will conclude this paper by giving in full the Will of Elizabeth Lorde, the last Prioress. Her brother, Brian Lorde, of York, had previously left her much money and goods.

"January 28th, 1550, Elizabeth Lorde, in Yorke, First I give and bequeathe my saull to God Allmyghtie, my creator and redeemer, with his most precious bloode, and to our blissed ladie Sancte Marie the Virgyne, and to all the holie and blissed company of heaven for to pray for me, and with me to God the Father Allimyghtie, and my bodie to be buried in the grounde within the Churche of the Holy Trinitie in Gotheromgate (York) in the ladie quere, nighe unto my broder's stall in the said Churche. Unto the poor people boxe in the said Churche 5 shillings. Also I will that these shall be bestowed at the day of my beriall four poundes and more after the discretion of my executours. Unto my cousyng Frances Gaile my best standyng pece gilt, with a cover and ten pounds. To my cousyng Robert Pecocke and ladie Anne, his wif, a standyiig pece gilt (705 pennyweights) with a cover, and to herself more foure angels in gold. To my cousyng Rauf Haull and Isabel, his wif, another standyng pece gilte with a cover, and to her more, foure angels in gold. To my cousyng Briane Lord, a goblet with a cover parcell gilte and five poundes. To my cousyiig John Rokelye and Dorothie, his wif, another goblet parcell gilte without a cover and to herself more in money foure poundes. To my cousyng Christopher Clapham and Alicie his wif, another goblet parcelle gilte without a cover, and to herself more in money foure poundes. To my cousyng Robert Garbray and Elizabethe his wife, a salt parcell gilte and half a dosand silver spoynes, and to herself more in monaye foure poundes. To Jennett Cooke the wif of Miles Cooke a macer. To my cousyng Ursula Gaile a silver pott and twenty poundes in monaye towardes her mariadge. To my cousyng Thomas Gaile, ten poundes. To my cousyng Mabell Wilson, the wif of Henry Wilson in Kendall, a pair of corall-beades with silver gaudes, and a ring of gold with a blewe sapher in it. To my cousyiig Thomas Lord, the son unto my broder Edward Lord forty shillings. To —. Shepard the wife of Laurentie Shepard in Kendall, and daughter unto my suster Margarete, a kirtyll and a petticote. To my cousyn John Lund forty shillings, and to Isabell his wif my best gowne and best kirtyll. To my cousyng Thomas Broides 20 shillings; and to Marie his wif a gowne, and a kirtyll next unto the best. To Sir William Garnett the parson my curate one old riall of gold to pray for me, and for tythes or offrynges nedigently forgettyn in discharge of my conscientic. To every one of the men servauntes and women servauntes in my broder's house two shillings a pece. To Elizabeth Bakehouse and Agnes Frankeland either of them a white petticote. To every god childe that I chrystened in Yorke, which are on lyve (in life) four pence a pece. To my cousyng Edward Harlyng 6s. 8d.; to my cousyng Katherine Harlyng, the wif of John Carlell 6s. 8d.; To Agnes Barton, Alicie Thornton, Johan Andrew, and Margerie Browne, which was susters with me in the howse of Wilberfosse, to everye on(e) of them 6s.8d. To the mendyng of the highe waye in Kexby Lane ten shillings. Also I will that my executour shall distribute for my saull to be praid for, foure poundes, which he shall order and dispose it at all times, at his own will and pleasour, without any accomple therefore gyving, but as shall please hymself to do unto any man. The residue to my lovyng and kind broder Maister Georgie Gaile, alderman, whom I ordayn and make my only faithful executour of this my last will and testament. Thies beyng wittenes, specialy requisite thereunto, Maister George Haull, Chamberlayn of York then; Miaister Miles Cooke, marchaunte, Richard Holidaye with William Garnett my curate. Also to evierye one of my sisters Margarete and Mabbles childer 6s. 8d. a pece. To my cousyng Isabell Haull the wife to my cousyng Rauf, a gowne the whiche did buy for me at London. Also I will that every one of my witnesses have for theire paynestakyng for me, for a remembrance for to pray for me, and to make merie with all. To Isabell Lund, a kercheve. To Robert Aman wif a kerchieve. To Mother Masherudder, widow, a kercheve. To Maistress Garnett a white cap and a silke hat."

Her will was proved 20th February, 1551.

After nearly 400 years the men and women of today cherish the memories, acts, and deeds, of the monastics and think kindly of them. If they possess a house or a mansion near an ancient monastery, they generally associate it with their dwelling by giving it the same name. Even long distances between do not stand in the way, to wit, the modern mansion of Warter Priory is perhaps a mile from the original priory. And the dwellers in towns love to call their villas by such monastic names as Saint Osyths, Saint Bedes, Saint Katherine's, etc., etc.

The monastics had their faults like other men, but on the whole their character stands well to-day, notwithstanding the piles of infamy and untruths hurled at them by ignorant people or those interested in defaming them.

GEORGE BEEDHAM.

Stamford Bridge, York.

September, 1917.

The following appeared in the Hull Daily Mail - Tuesday 24 May 1921

GOLDEN WEDDING. MR AND MRS G. BEEDHAM, OF POCKLINGTON.

Mr and Mrs George Beedham, Pocklington. were the recipients of numerous congratulations on the occasion of their golden wedding, which was celebrated quietly during the week-end. They were married in London on the 20th of May. 1871. Mrs Beedham was the daughter of Mr Daniel Powell, decorative artist, whose work can still be seen at the entrance the British Museum. Mr. Beedham's father came from Norton Disney, Lincoln, to farm, at Gowthorpe, in 1844. He was well known as farmer, mechanic, and violin player.

MR BEEDHAM'S REMINISCENCES.

In 1857 Mr Beedham was with his father at the Malton Michaelmas Fair. There he saw the first Sir Tatton Sykes, and heard him talk a group of farmers for about ten minutes. Sir Tatton, born at Wheldrake, was sent to a school in London, close to Bolt-court, Fleetstreet, where often conversed with Dr Johnson, who was born in 1709.

In 1858 his father placed him under the tuition of Mr Carus Bedford, Trinity Vicarage, Micklegate. York, where he remained till 1861.

Mr. Beedham loved antiquarian lore, and Cripplegate was for him a fine field to revel in. In 1887 he opened the Great Northern Company's depot at Bread-street, Cheapside, and remained there till 1905, when retired. A few months after he lost his eldest son, George, who, as a volunteer was chief engineer of the submarine A8, which went down with 13 other men in Plymouth.

Mrs Beedham, now in her 76th year, has been an invalid for a few years.

Mr. Beedham, is still strong and hearty in his 77th year. On the 13th inst. he walked to Storwood and back - quite 16 miles. One his greatest pleasures is to wander into the rural districts, especially the Wolds, and enjoy his bent for the antiquities of the district. He believes that idleness the hardest of work and shortens life by attenuating body and mind.

Mr and Mrs Beedham are widely known in Pocklington and Stamford Bridge districts.

Further information on the Beedham family can be found here.

|