Newcastle Courant - Saturday 15 July 1899

[ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.]

OUTSIDE A GREY-WALLED CITY.

By HARWOOD BRIERLEY.

I left York by Walmgate Bar-the only bar in England with barbican complete. The old doors, wickets, and portcullis, too, still exist in a good state of preservation. This bar, with its square tower, and turrets at the angles, was erected in the reign of Edward I., the barbican in the reign of Edward III. Above the entrance on the inside, and partly supported on the stone pillars, is a domestic building of timber and plaster, of the time of Elizabeth. The arms of Henry V., England and France, quarterly, ornament the front of this bar, and those of the city the front of the barbican. Comparatively few of the tourists to York ever see this unique mediaevel building, though they generally know something about Micklegate, Monk, and Bootham Bars.

Walmgate Bar in York

I am in the pleasant suburb of Hull road. Never to speak of the churches on the inner side of the bar, there were at least three or four on the outer - St. Lawrence's, St. Edward's, St. Nicholas', and St. Michael's, only the remains of the first one now existing alongside a magnificent new daughter church. Immediately without the bar there is a Thursday cattle-market held, and, when I passed by, the stalls appeared to be already filled. On the road past the Roman institution for Poor Clare's Colettines I met nigh a hundred herds of cattle coming to market at the indifferent rate which is peculiar to them, and lowing in the general confusion made by dogs, irate drovers, and vehicular traffic. These villa residences are delightful, and occasionally there are pretty cottages bearing boards above their lintel inscribed with silver on a sky-blue ground, 'Bedding plants and cut flowers for sale." In the neighbourhood of woodlands and crow-trees I passed an ancient place called Bees Wing, which although Beeswing was once a favourite place suggested the hum of bees and the general drowsiness of summer rather than reddish brown ale or blue tobacco fumes. The roads were wet, but drying up rapidly, and they were covered all over with the hoof-marks of passing beasts.

Walmgate Bar in York

I was in sympathy with the broken farm procession coming along that broad road between the clipped hedgerows towards the hoary-walled city. These things, instead of soldiers as of yore! There were carts and cattle for three or four miles, often a little mixed up, too; and the latter, like gentle ladies, preferring the foot- path itself. Milk cows, roan and white; steers and stirks, shaggy black; a flock of pearly sheep; and all pattering in the mud, or among the crisper embroideries of fallen leaves. Portable and not very spacious cattle pens above board, on the top of a grey-painted cart. Now, two pigs, netted over in the back portion of a farmer's trap. Odd figures a-foot, behind a bleating flock, in such antiquated hats and frocks as one sees in the old prints or paintings. Three human figures huddled a-row in the front of a rural contrivance. Two boys possessed of balloon cheeks driving a herd of bullocks with sticks every bit as big as alpen-stocks. A load of sheep, netted over, in a kind of coal-cart once painted red and blue, and compressed as tightly as herrings in a box. Everything was going citywards to pack a market already overstocked.

York Market at the turn of the century

On market-days more than a hundred quaint carriers' waggons come crawling into the city from every point of the compass. The Wilberfoss, Kexby, and York carrier passes me two figures are seen peeping out of the door-window behind; on the top are a few yellow boxes and baskets. This is William Hoop's Thursday van, and it is on its way to the Malt Shovel inn, in Walmgate. The Stamford Bridge, Gate Helmsley, and York carrier next passes me at an indifferent rate. This is a red-painted van, and it plies the road every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday, now being on its way to the "King's Arms" on Foss Bridge, which it will leave on the return journey at three o'clock in the afternoon, tinder the drivership of Mr Dickons or his wife. All these carriers' conveyances appear to be half of the gipsy caravan type and half of the omnibus type, so that speed is not a necessary qualification for patronage, and racing is unknown. A big man may travel many, many miles in one of them for sixpence, and get all the old butter-woman's talk for nothing. A snowy Christmas Eve spent in one of them on the quiet country roads would doubtless be a Christmas Eve well spent. I pass Grimston Hill House, the residence of Mr Samuel Border, Lord Mayor of York. Beyond it, there are the extensive chicory-fields of Dunnington. A single firm in York apparently does all the chicory buying, washing, drying, and roasting. The plant in its prime resembles the mangel wurzel. Many horses will devour it: coffee-drinkers prefer it in moderation.

T hen there is the Dunnington Windmill. It has a black body, four white sails, fantail to accommodate the changeable winds, and to prevent those four white sails being wrenched off; white little doorway and white little windows, which show that the building is four stories high. The mill-yard is a field, where the watch-dog is chained; by the road-side is the Windmill Inn, and J. W. Oxtoby-happy man! - is the sole proprietor of the lot. I entered this cottage inn by a rustic arbour and porch of rough branches, finding it (like a Kentish little place) covered with the leaves of the hop-vine, on the ruddle-red tiled floor being-alas! - four black-leaded spittoons filled with sand. The domestic arrangements allowed the inn-kitchen and house-place to be all in one, where, with his back to the chimney, I found the miller landlord in dusty white clothes taking his forenoon pipe and refresher. Into the windmill I went, seeing oats and barley ground together, and purling out into the bin in a yellow-white stream. I was taken up the slim, worn ladder steps to the topmost storey. When a gust of wind came, the sails spun round quicker, and the grinding Sound was more severe. There is something about these windmills of the East Riding, as about the water-mills of hillier districts, that one cannot help liking. They are not picturesque only but a painter, poet, or any other dreamer might almost in his dreams imagine that if flour were made in them his bread would be whiter than that made from flour turned out of the big steam roller mills. hen there is the Dunnington Windmill. It has a black body, four white sails, fantail to accommodate the changeable winds, and to prevent those four white sails being wrenched off; white little doorway and white little windows, which show that the building is four stories high. The mill-yard is a field, where the watch-dog is chained; by the road-side is the Windmill Inn, and J. W. Oxtoby-happy man! - is the sole proprietor of the lot. I entered this cottage inn by a rustic arbour and porch of rough branches, finding it (like a Kentish little place) covered with the leaves of the hop-vine, on the ruddle-red tiled floor being-alas! - four black-leaded spittoons filled with sand. The domestic arrangements allowed the inn-kitchen and house-place to be all in one, where, with his back to the chimney, I found the miller landlord in dusty white clothes taking his forenoon pipe and refresher. Into the windmill I went, seeing oats and barley ground together, and purling out into the bin in a yellow-white stream. I was taken up the slim, worn ladder steps to the topmost storey. When a gust of wind came, the sails spun round quicker, and the grinding Sound was more severe. There is something about these windmills of the East Riding, as about the water-mills of hillier districts, that one cannot help liking. They are not picturesque only but a painter, poet, or any other dreamer might almost in his dreams imagine that if flour were made in them his bread would be whiter than that made from flour turned out of the big steam roller mills.

Was it not R. L. Stevenson who said that a Scotsman may tramp the better part of Europe and the United States, and never again receive so vivid an impression of foreign travel and strange lands and manners as on his first excursion into England. The change from a hilly to a level country strikes him with delighted wonder. Along the flat horizon there arise the frequent venerable towers of churches. He sees at the end of airy vistas the revolution of the windmill sails. He may go where he pleases in the future; he may see Alps, and Pyramids, and lions; but it will be hard to beat the pleasure of that moment. There are, indeed, few merrier spectacles than that of many windmills bickering together in a fresh breeze over a woody country; their halting alacrity of movement, their pleasant business, making bread all day with uncouth gesticulations; their air, gigantically human, as of a creature half alive, put a spirit of romance into the tamest landscape. When the Scotch child sees them first he falls immediately in love; and from that time forward windmills keep turning in his dreams.

At the small village of Kexby there is a little church in the Early English style, built by Lord Wenlock. There, too, a substantial stone bridge is thrown over the Derwent, one of Yorkshire's chief rivers. Looking over the left parapet, the river below is seen as a good broad flood, bluely reflecting the sky; on the opposite side it appears whitish green. On both sides alike, it is seen winding its course across the levels for a goodly distance, though not as if it had quite made up its mind which way to flow. There is nothing here of the Swale and Wharfe in their higher reaches, as they make their never-ending, ever-racing merry din, yet the Derwent at Kexby is not at all sluggish, and not with- out excellent table-fish.

The Barker Carrier from Stamford Bridge to York,

seen here in Dunnington

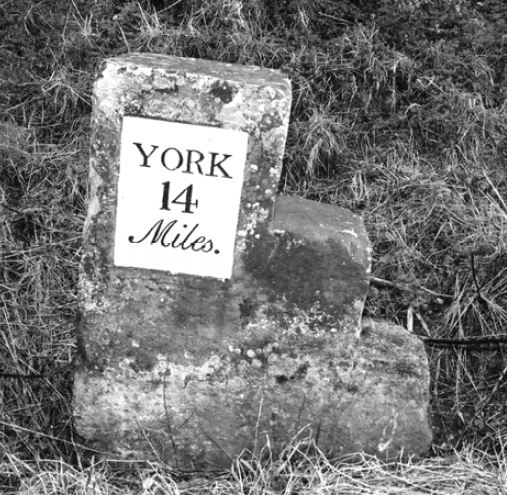

Yonder, on the low pastures, are evidences of recent floods not yet subsided, water still being up to the bottom bars of a long row of wooden railings. Pollard willows are on the banks, all shapely and still green. There are one or two farms, and trees sheltering them, and golden hay-ricks clustering around. To the east a slight ridge wooded, and the tips of a windmill seen bobbing over it as the sails go merrily round. A house in the vicinity was the scene of Henry Crossley's story "The Swell Mobsman." A white six-barred gate. A row of five black telegraph-posts and two wires. The road bending between its swarded sides, and suddenly disappearing.  Where it disappears, a row or a dozen trees, planted obliquely. A white cottage by the side of them, and a white post pointing towards the Cattons. A field of turnips to leftwards. A black dog trotting across the stubble to rightwards. A flight of sparrows twittering as they go from hedge to hedge. An old milestone, three steps to the top, having in front an iron plate riveted to the stone, and saying. "Beverley 22, York 7." Where it disappears, a row or a dozen trees, planted obliquely. A white cottage by the side of them, and a white post pointing towards the Cattons. A field of turnips to leftwards. A black dog trotting across the stubble to rightwards. A flight of sparrows twittering as they go from hedge to hedge. An old milestone, three steps to the top, having in front an iron plate riveted to the stone, and saying. "Beverley 22, York 7."

On the left, far away, a range of shadowy wolds. There is a single figure coming along the road towards me. It is the figure of an attenuated old man, with beard as white as Father Christmas's own, and he carries a carpet bag and a bass. Alms he feebly solicits, and then, seeing by my countenance that I am disposed to stop and listen to his woes, he immediately lays down bag and bass in the road. Very nearly all the colour has gone out of those light blue eyes; the owner of them has begun to stoop. For he is a septuagenarian Journeyman pine-maker, afflicted with rheumnatics and at the time of speaking he carries a porous plaster on the left hip. My honest wayfarer, who has walked all the way from Grimsby, is on his way to York and the big West Riding towns beyond. Had been at Grimsby breathing fishy air for turned four months, making 13- inch pipes at 1s 3d per gross , of sixteen dozen to the gross. His week's work - no child's play - consisted of turning out six gross of pipes that size, Actual earnings, 7s 6d. out of which he had - pay 2s 6d for lodgings. "It's a bread and cheese job, sir. is clay pipe making," said he; "there wants an alteration made somewhere" "But," objected I, "as teetotalism spreads, perhaps the consumption of tobacco, and hence the purchasing of pipes - "Aye, sir, I know what you would say. But hasn't smoking grown with teetotalism? I think tobacco has taken the place of snuff, too." - I pulled a sixpenny wood pipe out of my pocket. "There, now, look as that." came the old fellow's comment. "It cost the manufacturer less than a penny, yet you had sixpence to pay for it. A journeyman's wages are 1s 5½d for sixteen dozen clays of a particular size. You could buy twelve such pipes of a retailer for the price of your wooden one: so, where's your profit for the journeyman? Why doesn't some big lord set the fashion of smoking commion clays-another Lord Tennyson, now for there's nothing half so sweet and good as a clay. A wood pipe slow poison, sir."

I am now half way between York and Pocklington- the picturesque old market town whose Grammar School William Wilberforce attended. One of the master's houses is known as the "Wilberforce Lodge," and it was there that the eminent philanthropist penned a letter, whilst in his fourteenth year, to a York newspaper, in which he first denounced "the odious traffic in human flesh."

|