|

The town of Pocklington takes its name from an Anglian settlement of Pocela's people, but it may be even older than that name suggests.

There is certainly evidence of earlier habitation nearby and ancient earthworks and tumuli abound in the Wolds region. The area round Arras, at Market Weighton, was believed to be the site of a major prehistoric battle, lending credence to early habitation, and the Parisi tribe of ancient Britons, which included the legendary Queen Boudicea, had a regional capital around this area. Millington, Goodmanham and Londesborough are all claimants for the lost Roman town titled Delgovitia. Vikings likewise left a mark on the region, and the Nunburnholme Stone in the village church is a 9th century carved Viking relic.

Saint Helen’s Well

Chapel Hill was an outstanding beauty spot in Pocklington, and many of the local residents strolled up there on a weekend to picnic, especially as an Easter celebration along with rolling eggs.

Such practices belong to the dim past of pagan activities, and many pagan sites and rituals were merged into Christian rites as that religion took hold.

With water being a necessity of life, the springs and watering places themselves had special significance in the lives ol people. Wells, and springs were sacred sites, and the blessing ol water supplies formed a major feature of many religions.

In Pocklington. the well on Chapel Hill was latterly dedicated to the Christian Saint Helen, after Helena the mother of Emperor Constantine. She was responsible lor the rededication of many pagan sites as she look them inlo the new religion she had embraced.

The well itself may have firstly been dedicated to Elen. a pagan Celtic goddess, a nature spirit or fertility symbol, whose origins are linked with the mysterious King Arthur. The truth is as shrouded in mystery as were those days of the Dark Ages. Appeasing water spirits and. by implication, ensuring fertility, was a preoccupation of peoples whose very life depended on nature, and the crop cycle.

Water in such wells was always believed to have magical and healing properties, and the water in St Helen's Well was often drunk in the expectation of curing minor ills, or at the very least ensuring a measure of the protection of whichever god the drinker subscribed to.

Given the importance of wells, many had chapels and hermitages attached, and St Helen's was no exception. Indeed, the site which was originally Primrose Hill takes its name from the small chapel built close to the well's site. Although the wooden chapel is now lost, having been neglected and forgottenoverlheyears, it was still in use in the early 19th century.

With current housing development threatening the site even further, the Pocklington Civic Trust purchased a small area of land containing the well, to preserve it from further destruction. Although attempts to have it scheduled as an ancient monument failed, given the lack of archaeological evidence found by the inspector, the Trust still hopes to arrange lor the excavation and restoration in due course.

After the Norman Conquest, in which the Battle of Stamford Bridge played a major role, Pocklington is mentioned in the famous Domesday Book as one of only two East Riding boroughs. Before that time, the Manor had been held by the Earl Morcar, and valued at £56. By 1086, although the town boasted three water mills, probably for corn grinding, the value of the borough was reassessed at a mere £8.

Pocklington was originally a predominantly agricultural town, lying between two Roman roads. It has always played an important part in the East Riding life, but its geographical location within an area bounded by marshes, in some measure protected it from outside interference.

The readily available water gave rise to corn milling in the 11th century, and later supported the growing woollen industry. A fulling mill stood on the Ings at Ousethorpe, alongThe Mile, and later, in the 13th century weaving made its mark, including the hemp necessary in ropemaking. Many wealthy woollen merchants lived and traded in the town. One of the foremost was Thomas de Berewick, who bought Yorkshire wool for the King and in the early 1300s recorded a contract of loans for £40,000

The prolific Wolds crop, barley, fed the malting and brewing industry, which became a large scale operation by 1550.

Cattle raising and butchering was another staple industry for the town, and the trades associated with that, skinning and tanning, being a major source of employment.

With the coming transport and industrial revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries, little changed for Pocklington. The York-Beverley turnpike road constructed in 1764 did not pass through the town and the navigable canal of 1815 only reached the turnpike road, increasing this sense of independence. Even the railway was considered a branch line, mainly to connect the Londesborough Estate of George Hudson the railway king with his York base. The semi-isolation continued, with Pocklington's persistence in holding its Saturday market when many larger towns competed on the same day for trade. At that time, Pocklington was drawing its custom from an area only some six miles in radius. The poor road system and marshy surroundings made journeys, particularly in winter, quite hazardous.

From the 1850s, a time of consolidation.

In 1900, a newspaper of the day had coined the title 'Woldopolis' to describe the town. Pocklington had by that time developed a strong sense of civic pride after an uneasy time in the 1850s. Local government was at that period in a state of chaos, still under the control of the Vestry Meeting and the Manor Court. The Urban District Council made its appearance by 1894, and as the 19th century got underway, the town went through a period of consolidation after a rapid growth in population.

Census figures for the day show 2,546 citizens in 1851. rising to 2.733 by 1881. Twenty years later, this figure had dropped by 270. mainly due to movements to larger towns and to emigration. By the 1890s many Pocklingtonians had settled in North America, South Africa and Australasia.

As far back as 1851. records show 49% of the population to be born in the town. 42% other parts of in Yorkshire, and 9% elsewhere. Of the latter, were 50 Irish settlers mainly living in the workhouse or lodgings.

Milling. brewing, malting and ropemaking were the only traditional town industries then surviving, weaving and tanning had died out. Some leather trade persisted, with fellmongers. glovers, saddlers and shoemakers active. The occupations included in the census record no less than 6 ministers of religion. 4 lawyers. 18 innkeepers. 1 superintendent of paupers. 168 farm labourers and. oddly. 2 sailors. The major employer was builder Thomas Grant, who had 10 men.

The town was growing. By 1857 the overcrowded churchyard was closed, and the Rural Sanitary Authority formed in 1876. which improved the health of townspeople. In 1889 a water company brought much needed fresh water, but slop water and water closets still ran into the beck which ran open through the town, and eventually into the grammar school's mill-dam - an open cesspool and health hazard. 1897 marked a turning point with the installation of a sewerage system, and the culverting of the beck..

A Wild West flavour was pictured in a Pocklington event of the 1950s. The mounted trio of cowboys form part of the Corker's Rag procession, that traditionally formed the basis of the July Gala day for the town. A Wild West flavour was pictured in a Pocklington event of the 1950s. The mounted trio of cowboys form part of the Corker's Rag procession, that traditionally formed the basis of the July Gala day for the town.

The Cork Club - Corkers as they came to be known - was a group of like minded people who raised funds for various charitable purposes in the town, particularly to help those fallen on hard times. As their Gala programme stated: 'In a welfare state, a man who is true to his better self and prompted by love of his fellow man cannot rest content to leave the State to dispense relief by schedule to its less fortunate members, but must find some outlet for his finer instincts to enable himself to bring health, happiness and comfort to his brother man. Hence such a man combines with others similarly prompted into an organisation such as the Cork Club which, by sacrifice of time, leisure and money, takes care of our brethren in distress'.

The Gala covered a diversity of activities suitable for a summer day. One fifties programmed described how, in the afternoon, a highland pipe band led a parade through the town, followed by wheelbarrow and pram races from Figg's Garage to Railway Street. There were fancy dress competitions. Gala Queen, dog show, tug-of-war and sheep dog demonstrations.

As the parade reached Burnby Hall's sports field, it was time for American Square dancing, a visit to the baby show or the menagerie, or a gentle watch of the sheaf throwing competition. It all ended with a motor cycle display billed as 'thrills with flames'.

Pocklington still continues a fine tradition of supporting charity and worthwhile causes, with groups such as Lions, Truckers, Round Table, The British Heart Foundation, the Defibrillator Appeal, the Sandra Kay Trust, Children's causes, animal welfare, the blind, the disabled, and many, many more.

But in spite of this, Pocklington proved a popular place to live, just as it does today, gaining a reputation for gentility in the 18th century, and in 1740 including a library for gentlemen of the town. Yet Pocklington's tranquillity was soon to be shaken, with the coming of the Enclosures Act in 1757. Life would never be the same for rural Pocklington.

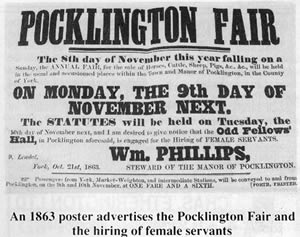

The Hiring Fairs of Martinmas, held in November, were the annual opportunity for farm and domestic workers to have a new job or recontract for their existing one.

Farmhands had a fortnight free at the end of their working year, and flush with a year's pay - less any deductions - they would troop into Pocklington to spend their wages. When all that merriment was done with, the willing, and not so willing, workers lined themselves up for the highest bidder. The deal, when struck with a prospective employer, was sealed by a handshake and the exchange of I/-, known as a Feste.

The worker's clothes, often housed in a tin trunk, were then taken to the new place of employment, ready for the start of the working year.

A year that was to be faced without  wages until the next hiring fair - unless of course the employer would agree to a 'sub' in advance. wages until the next hiring fair - unless of course the employer would agree to a 'sub' in advance.

A poster, dated 1863, gave notice of the town fair, for trading horses, cattle, sheep and pigs, and the hiring of female servants. Separately, one hopes!

In 1909, it was recorded that: 'The annual statute hirings were held on Wednesday, with men and boys attending in large numbers, but not seemingly keen on getting hired. The wages were generally the same as last year; Farm Foremen £25-£30; Shepherds £19-£27; Waggoners £ £24; Third Lads £16 10s-£19 10s; Beastmen £18-£23; Young Lads £6 10s-£9 10s.

There was also a good attendance of female servants and mistresses, the latter being faced with the same demand as last year-higher wages. Many of the females expressed a desire to go to the large towns. Girls from school command fees from £7 10s-£10; experienced girls £15-£18. Cooks £16-£20; First class girls command up to £22 per annum including board and lodge!

After a period of steady development through the Middle Ages, Pocklington continued to grow and expand in trade and housing through to the 19th century.

At that period, much of the town was rebuilt, and trade had an upsurge when the canal was built. An Act of Parliament in 1814 allowed for the construction of a navigable canal from Hast Cottingwith to Street Bridge, one mile outside Pocklinglon. This brought to the town coal. lime, manure, and merchandise of all kinds for the local traders. In return, the barges took away corn, flour, timber and assorted articles for sale elsewhere.

Tradesmen at this time had their best week of the year at the annual hirings, where the labourers and domestic servants spent their years wages and sampled the delights of roundabouts, wild beast shows and stalls of every description.

By the end of the century, hirings declined in popularity, and fairs were replaced by the annual Horse Show and races on May 2nd. and a Floral Show. The Saturday market was growing less popular. with only some dozen stalls. The town's fortunes were changing and altering, giving it importance and status that even some larger settlements lacked.

The Oddfellows. Victoria and Central Halls provided entertainmcnl for the town. with lectures, temperance meetings (a feature of a town with eight public houses!) and home for the Literary and Philosophical Society. The Salvation Army Barracks on Chapmangate were destroyed by a disastrous fire in 1896, and the Victoria Hall which replaced them, brought the first cinematograph to the town in 1900.

As the first World War drew nearer, the town was dominated by wealthy traders, shopkeepers, solicitors, doctors, and craftsmen. It was self sufficient in facilities and chic amenities, hail thriving schools and a respected educational system. The Lord of the Manor hail transferred to Kilnwick Percy Hall, hut the large estates owned by the county's gentry and nobility offered employment and parkland for the benefit of the population.

The years of depression following that great conflict brought greater change in the town's fortunes. The market died, and social amenities were stretched to the limits. But Pocklington was only temporarily down - not out - and set to rebuild itself to enter the 20th century.

IN COMMON with all parts of the country, Pocklington faced a difficult period during the dark years of the Second World War. The town stood virtually in the centre of a massive ring of airfields which included Full Sutton. Melbourne. Elvington. Rufforth. Driffield and Holme-on-Spalding, with Pocklington airfield opened in June 1941. Residents grew to have a love hate relationship with the drone of airplane engines and the influx ol airmen stationed on the doorstep. . The first ever squadron lo use Pocklington as a base was 405 Royal Canadian Air Force, equipped initially with Wellington Mk2s. and later with the Halifax Mkl The 102 "Ceylon" Squadron armed in August ‘42 (as 405 departed) and were constantly employed in raids and mine laying operations throughout the war. Planes From ihe squadron look part in the famous ‘1.000 bomber raids' on Duisberg.

In October "43. a Halifax Mk2 crashed just over three miles south-east of Pocklinglon. killing its crew of seven, an incident well remembered by people in and around the town. Another Mk3 from ihe base crashed in Gloucester, also killing ihe crew, during a diversion flight in 1444. One losing power in an abortive take-off attempt al Pocklinglon. crashed, injuring a crewman, and yet another Mk2 went missing over the North Sea during a practice bombing session.

The New Year of 1945 started on a gloomy note with three Halifaxes lost in accidents. In the January, one hit a house in the undershoot area near Pocklington. and the following day a second aircraft was written off after it overshot the airfield, snapping off its undercarriage when an engine leathered.

By late 1945. the airfield became the 17 Aircrew Holding Unit, with 102 Squadron converting to Liberators.

In all, the brave men who manned the base and flew the aircraft from Pocklington with 102 Squadron gained 6 DSOs. 132 DFCs.3bars to DFC.and 36 DFMs. before leaving the town in September "46.

The history of all the local airfields is chronicled in a magnificently illustrated book. White Rose Base, by Brian J Rapier. A York Air Museum publication.

|