|

Image from: Wikimedia Commons |

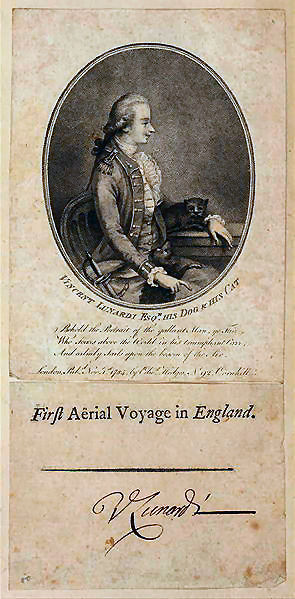

The English historian of aerostation gives some details of the first aerial voyage made in this country by the Italian, Vincent Lunardi.

The balloon was made of silk covered with a varnish of oil, and painted in alternate stripes--blue and red. It was three feet in diameter. Cords fixed upon it hung down and were attached to a hoop at the bottom, from which a gallery was suspended. This balloon had no safety-valve--its neck was the only opening by which the hydrogen gas was introduced, and by which it was allowed to escape.

In September, 1784, it was carried to the Artillery Ground and

filled with gas. After being two-thirds filled, the gallery was

attached with its two oars or wings, and Lunardi, accompanied by

Biggin and Madame Sage, took his place; but it was found that the

balloon had not sufficient lifting power to carry up the whole three, and Lunardi went up alone, with the exception of the

pigeon, the cat, and the dog, that were with him.The balloon rose to the height of about twenty feet, then

followed a horizontal line, and descended. But the gallery had

no sooner touched the earth than Lunardi threw over the sand that

served as ballast, and mounted triumphantly, amid the applause of

a considerable multitude of spectators.

|

Vincenzo Lunardi's balloon exhibited at the Pantheon in Oxford Street, London circa 1783.

Image from: Wikimedia Commons |

After a time he

descended upon a common, where he left the cat nearly dead with

cold, ascended, and continued his voyage. He says, in the

narrative which he has left, that he descended by means of the

one oar which was left to him, the other having fallen over; but,

as he states that, in order to rise again, he threw over the

remainder of his ballast, it is natural to believe that the

descent of the balloon was caused by the loss of gas, because, if

he descended by the use of the oar, he must have re-ascended when

he stopped using it. He landed in the parish of Standon, where

he was assisted by the peasants.

He assures us again that he came down the second time by means of

the oar. He says:--"I took my oar to descend, and in from

fifteen to twenty minutes I arrived at the earth after much

fatigue, my strength being nearly exhausted. My chief desire was

to escape a shock on reaching the earth, and fortune favoured

me." The fear of a concussion seems to indicate that he

descended more because of the weight of the balloon than by the

action of the oar.

|

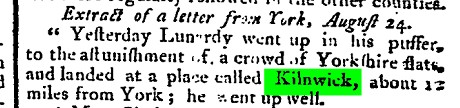

A newspaper reference of Lunardi's flight in August 1786 from York Races to Kilnwick near Pocklington. From: Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser (London, England), Tuesday, August 29, 1786 |

It appears that the only scientific instrument he had was a

thermometer which fell to 29 degrees. The drops of water which

had attached themselves to the balloon were frozen. The second aerial journey in England was undertaken by Blanchard

and Sheldon. The latter, a professor of anatomy in the Royal Academy, is the first Englishman who ever went up in a balloon.

This ascent was made from Chelsea on the 16th October, 1784.

The same balloon which Blanchard had used in France served him on

this occasion, with the difference that. the hoop which went

round the middle of it, and the parasol above the car, were

dispensed with. At the extremity of his car he had fitted a sort

of ventilator, which he was able to move about by means of a

winch. This ventilator, together with the wings and the helm,

were to serve especially the purpose of steering at will, which

he had often said was quite practicable as soon as a certain

elevation had been reached.

The two aeronauts ascended, haying with them a number of

scientific and musical instruments, some refreshments, ballast, &c. Twice the ascent failed, and eventually Sheldon got out, and

Blanchard went up again alone.

Blanchard says that, on this second ascent, he was carried first

north-east, then east-south-east of Sunbury in Middlesex. He

rose so high that he had great difficulty in breathing, the

pigeon he had with him escaped, but could hardly maintain itself

in the rarefied air of such an elevated region, and finding no place to rest, came back and perched on the side of the car.

After a time, the cold becoming excessive, Blanchard descended

until he could distinguish men on the earth, and hear their

shouting. After many vicissitudes he landed upon a plain in

Hampshire, about seventy-five miles from the point of departure.

It was observed that, so long as he could be clearly seen, he

executed none of the feats with his wings, ventilator, &c., which

he had promised to exhibit.

Enthusiasm about aerial voyages was now at its climax; the most

wonderful deeds were spoken of as commonplace, and the word "impossible" was erased from the language. Emboldened by his

success, Blanchard one day announced in the newspapers that he

would cross from England to France in a balloon--a marvellous

journey, the success of which depended altogether upon the course

of the wind, to the mercy of which the bold aeronaut committed

himself.

A certain Dr. Jeffries offered to accompany Blanchard. On the

7th of January the sky was calm, in consequence of a strong frost

during the preceding night, the wind which was very light, being

from the north-north-west. The arranged meets were made above

the cliffs of Dover. When the balloon rose, there were only A certain Dr. Jeffries offered to accompany Blanchard. On the

7th of January the sky was calm, in consequence of a strong frost

during the preceding night, the wind which was very light, being

from the north-north-west. The arranged meets were made above

the cliffs of Dover. When the balloon rose, there were only

three sacks of sand of 10 lbs. each in it. They had not been

long above ground when the barometer sank from 29.7 to 27.3. Dr.

Jeffries, in a letter addressed to the president of the Royal

Society, describes with enthusiasm the spectacle spread out

before him: the broad country lying behind Dover, sown with

numerous towns and villages, formed a charming view; while the

rocks on the other side, against which the waves dashed, offered

a prospect that was rather trying.

They had already passed one-third of the distance across the

Channel when the balloon descended for the second time, and they

threw over the last of their ballast ; and that not sufficing,

they threw over some books, and found themselves rising again.

After having got more than half way, they found to their dismay,

from the rising of the barometer, that they were again

descending, and the remainder of their books were thrown over.

At twenty-five minutes past two o'clock they had passed

three-quarters of their journey, and they perceived ahead the

inviting coasts of France. But, in consequence either of the

loss or the condensation of the inflammable gas, they found

themselves once more descending. They then threw over their

provisions, the wings of the car, and other objects. "We were

obliged," says Jeffries, "to throw out the only bottle we had,

which fell on the water with a loud sound, and sent up spray like

smoke."

They were now near the water themselves, and certain death seemed

to stare them in the face. It is said that at this critical

moment Jeffries offered to throw himself into the sea, in order

to save the life of his companion.

"We are lost, both of us," said he; "and if you believe that it

will save you to be lightened of my weight, I am willing to

sacrifice my life."

This story has certainly the appearance of romance, and belief in

it is not positively demanded.One desperate resource only remained--they could detach the car

and hang on themselves to the ropes of the balloon. They were

preparing to carry out this idea, when they imagined they felt

themselves beginning to ascend again. It was indeed so. The

balloon mounted once more; they were only four miles from the

coast of France, and their progress through the air was rapid.

All fear was now banished. Their exciting situation, and the

idea that they were the first who had ever traversed the Channel

in such a manner, rendered them careless about the want of

certain articles of dress which they had discarded. At three

o'clock they passed over the shore half-way between Cape Blanc

and Calais. Then the balloon, rising rapidly, described a great

arc, and they found themselves at a greater elevation than at any

part of their course. The wind increased in strength, and

changed a little in its direction. Having descended to the tops

of the trees of the forest of Guines, Dr. Jeffries seized a

branch, and by this means arrested their advance. The valve was

then opened, the gas rushed out, and the aeronauts safely reached

the ground after the successful accomplishment of this daring and memorable enterprise.

A number of horsemen, who had watched the recent course of the

balloon, now rode up, and gave the adventurers the most cordial

reception. On the following day a splendid fete was celebrated

in their honour at Calais. Blanchard -was presented with the

freedom of the city in a box of gold, and the municipal body

purchased the balloon, with the intention of placing it in one of

the churches as a memorial of this experiment, it being also

resolved to erect a marble monument on the spot where the famous

aeronauts landed.

Some days afterwards Blanchard was summoned before the king, who

conferred upon him an annual pension of 1,200 livres. The queen,

who was at play at the gambling table, placed a sum for him upon

a card, and presented him with the purse which she won.

|