|

Thomas Cooke reluctantly began his working life early in the nineteenth century as a young Pocklington shoemaker. But he had such an aptitude for learning and making things that he was able to teach himself mathematics and become a schoolmaster, then experiment with home-made telescopes. From these humble beginnings, within a few years he had established himself as the world’s foremost maker of telescopes. Amongst his numerous engineering achievements he made the world’s biggest telescope and the world’s most accurate clock, created an observatory for the royal family, and he even tried his hand at manufacturing  early steam-driven cars. early steam-driven cars.

Cooke was born in Allerthorpe in 1807. Years later his wife outlined his early upbringing: “The son of a working shoemaker at Pocklington. His father’s circumstances were so straightened that he was not able to do much for him; but he sent him to the National school, where he received some education. He remained there for about two years, and then he was put to his father’s trade.”

Shoemaking was not a particularly lucrative business, but it was reliable and honourable and for centuries was one of the main trades in and around Pocklington, with one of the town’s seven annual fairs devoted to the sale of boots, shoes and other leather goods. However, young Cooke did not take to his new employment: “He greatly greatly disliked shoemaking, and longed to get away from it.” He had heard of the exploits of Captain Cook, and inspired by the tales of Cook’s voyages he became eager to go to sea and spent all his spare hours learning navigation in order to become a seaman.

However, when he announced that he was ready to set out for Hull and find a ship, “the entraties and tears of his mother prevailed on him to give up the project”. Having his ambition to travel thwarted, but still not content to continue making shoes and boots, he “proceeded with his self-education and gathered together a good deal of knowledge. Everybody liked him, for his diligence, his application, and his good sense, and at the age of 17 he was employed to teach the sons of neighbouring farmers”. However, when he announced that he was ready to set out for Hull and find a ship, “the entraties and tears of his mother prevailed on him to give up the project”. Having his ambition to travel thwarted, but still not content to continue making shoes and boots, he “proceeded with his self-education and gathered together a good deal of knowledge. Everybody liked him, for his diligence, his application, and his good sense, and at the age of 17 he was employed to teach the sons of neighbouring farmers”.

He made such a success of being an impromptu teacher to the farmers’ sons of the Pocklington district, that only a year later he was able to open a village school at Bielby. He continued to teach others by day and learn himself by night, and soon moved his school from Bielby to Skirpenbeck.

At Skirpenbeck he met his future wife, who was one of his pupils, and five years his junior. Fifty years on she spoke of how her husband developed his brief rudimentary education into becoming a schoolmaster: “He first learned mathematics by buying an old volume from a bookstall with a spare shilling. He also got odd sheets, and read books about geometry and mathematics, before he could buy them; for he had very little to spare”.

But Cooke’s interest in mathematics and science was practical as well academic. He had also retained his interest in navigation and instruments, and while at Skirpenbeck he made his own first rudimentary telescope – grinding a lens by hand out of the bottom of a glass whisky tumbler, then mounting in into a frame that he soldered together from a piece of tin.

Cooke’s next step up was to move to York and become a mathematics teacher in the city. Now married and with a young family, he taught in two York academies and eked out his income by tutoring gentlemens’ sons in the evening.

That brought him into contact with some notable men of influence and learning. One, Professor Phillips, took possession of his first home-made telescope, and that led to his first commission to make another telescope for local attorney, William Gray.

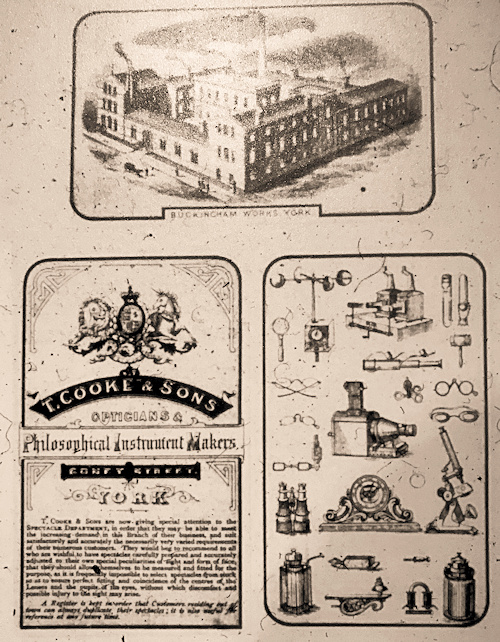

Though he continued to spend long hours teaching mathematics, he devoted any spare hours to making bigger and better telescopes. And in 1836 he ploughed his meager savings, augmented by a £100 loan from his wife’s uncle, into opening a shop in Stonegate for the manufacture of telescopes, spectacles and optical instruments.

The telescope had come to prominence in England in 1758, then exorbitant Government duty imposed on the manufacture of flint glass has just about killed the trade in England and all the best instruments now came from the continent. But Cooke’s instruments quickly established a reputation as being the best and cheapest in the country.

His expertise saw his telescopes rapidly become sought after across the globe, and the demand was such that he had to open a factory, The Buckingham Works, in 1855 to keep up with his orders. It was very much a family business with his brother and two sons involved in production.

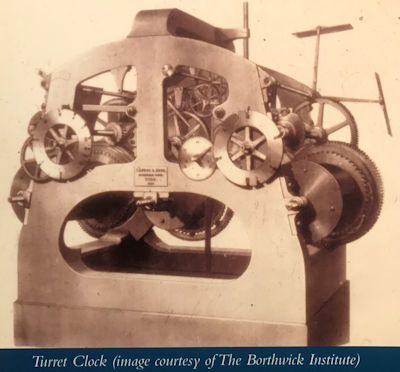

Cooke’s mathematical and creative accuracy and expertise, and natural ability to improve or invent just about anything mechanical also saw him become a skilled optician and maker of clocks, sun-dials and pumps. He supplied the machinery used to establish the pump-room at Harrogate spa, and made clocks of all shapes and sizes. Not only did his enormous turret clocks become popular across the country in the towers of churches, stately homes and Victorian factories, but he also made indoor case clocks, including the world’s most accurate timepiece of the time. He made surveying instruments, greatly in demand due to the growth of railways, ship’s sextants and other nautical instruments, early cameras and photographic lenses, and even tried his hand at manufacturing stream driven automobiles.

As always, Cooke was ahead of his time. At the York Exhibition of 1866 he demonstrated his three-wheeled, steam powered car which he claimed could carry 15 people at 15 mph for a distance of 40 miles. The vehicle duly performed to expectations and made a trip from York to Hull in a single day. There was one major problem – the traffic laws of the time only allowed speeds of 4 mph on country roads and 2 mph in towns, and required a man to walk in front of automobile to warn horse drawn vehicles. For a perfectionist like Cooke there was no point in compromise, so he simply dismantled the car and put his engine into a boat instead.

He may have been able to turn his hand to so many things, but his telescopes remained pre-eminent, and he was presented with a silver medal, the highest prize awarded, for a six-inch equatorial telescope at the first Paris Exhibition in 1855. His telescopes were supplied to most of the country’s astronomers, and a few years later he was summoned by Prince Albert to Osbourne, the royal retreat on the Isle of Wight, to discuss the setting up of an observatory for the royal family. Cooke subsequently manufactured and installed a telescope at Osbourne and went on to give Queen Victoria and her children lessons in astronomy. He may have been able to turn his hand to so many things, but his telescopes remained pre-eminent, and he was presented with a silver medal, the highest prize awarded, for a six-inch equatorial telescope at the first Paris Exhibition in 1855. His telescopes were supplied to most of the country’s astronomers, and a few years later he was summoned by Prince Albert to Osbourne, the royal retreat on the Isle of Wight, to discuss the setting up of an observatory for the royal family. Cooke subsequently manufactured and installed a telescope at Osbourne and went on to give Queen Victoria and her children lessons in astronomy.

Not only did Cooke make the world’s best and most accurate telescopes, but shortly before his death he established by some distance the world’s biggest. Cooke died in 1868 at the age of 62, just as he was putting the finishing touches to a six-ton, 32 foot long telescope with an aperture of almost 25 inches (the previous biggest of the time was in Chicago and measured 18 inches).

Though Cooke himself died at a comparatively early age, the Messers Cooke and Sons’ Buckingham Works carried on under the direction of his sons producing high quality telescopes, prismatic compasses and theodolites – Captain Scott’s ill-fated expedition to be first to the South Pole used Cooke & Sons instruments. They fitted out the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, and developed telescopic sights for the guns of the Royal Navy.

And the quality and precision of everything he made has guaranteed him immortality through his works. Remarkably, some of Cooke’s telescopes are still in daily use at leading observatories around the world, while nearer home there is one which he built in 1850 in the Yorkshire Philosophical Society observatory in York’s museum gardens. His case clocks and instruments are now prized by collectors as valuable antiques, while his church turret clocks look out across towns all over England, still telling the precise time. And his original optician’s shop from Stonegate also became preserved in time when it was rebuilt as part of the ‘Kirkgate’ Victorian street in York’s Castle Museum.

|